Hello all, what follows is Volume 1 of two very special mixes I made upon returning from the motherland: Uruguay. Truly, this was the best trip I’ve ever been on. Along with a little bit of background and history, here I try to capture the atmosphere and sentiment of me and my wife’s experiences through the sounds we listened to while there, as well as with what I was inspired to dig up and look into upon our return. By no means am I trying to bore anyone with vacation photos, nor is this a fully detailed account of any of the artists featured on the mix; for that matter, nor is this a thorough history of that wonderful little country nestled between the massive Brazil and Argentina, settled on the banks of a river as wide as a sea. It is, however, an attempt to communicate a certain vibration. Feel free to just press-play, sink in, and enjoy yourself.

Thanks,

Bobby Calero

P.S. I did the majority of the translations here, so don’t hesitate to chime in if you have a better suggestion, as knowing two languages is more automatic while translation itself is a slippery art form. Likewise, feel free to offer any information or corrections you might have on any of the various topics addressed here. Remember, in this (somewhat) instant field of self-publishing on a blog , there are no editors or proofreaders to rely on. —Enjoy!

[Note: This two-volume mix is best enjoyed when under the sun, so be sure to break it out a few times over the course of the summer!]

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

————-______________\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/

A MOUTHFUL OF PENNIES PRESENTS:

El Ambiente Bien Babes Y Bean de Uruguay: Volume 1

1) Let’s Go Away For Awhile – The Beach Boys (1966)

2) Sun King – The Beatles (1969)

3) Para Hacer Musica, Para Hacer – Miguel Y El Comité (1971)

4) Esa Tristeza – El Kinto (1968)

5) No Puede Ser – Los Campos (1972)

6) Hermano Americano – Montevideo Blues (1972)

7) And I Love Her – La Fragua (2001)] [Snippet]

8) Valentine Day – Paul McCartney (1970)

9) Jacinta – Eduardo Mateo (1972)

10) Fields Of Joy – Lenny Kravitz (1991)

11) La Conferencia Secreta del Toto’s Bar/Mi Tía Clementina – Los Shakers (1968)

12) African Bird – Opa (1976)

13) Barnyard/Old Master Painter/You Are My Sunshine – Brian Wilson (2004)

14) Principe Azul – El Kinto (1968)

15) Fly – Nick Drake (1970)

17) Hombre – Eduardo Mateo &Verónica Indart (1969)

18) Norwegian Wood (Baguala) – La Fragua (2001)

19) 4th Time Around – Bob Dylan (1966)

20) Zamba De Mi Esperanza – Jorge Cafrune & Los Chalchaleros (1964/2000)

21) Gioco di Bimba – Le Orme (1972)

22) Siempre Caminar – Limonada (1970) [Snippet]

23) Luna de Margarita – Simón Díaz (1966)

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

A MixTape by A Mouthful of Pennies (Bobby Calero).

Cover art and all personal photos by Keri Kroboth.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

————————(CLICK TO LISTEN & DOWNLOAD)

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[1) Let’s Go Away for Awhile – The Beach Boys (1966)]

[…] something everyone in the world must have said at some time or another. Nice thought; most of us don’t go away, but it’s still a nice thought.”

—Brian Wilson (Linett, 2001).

One stunning facet from the warm gem that is The Beach Boys’ masterpiece Pet Sounds. It is physically impossible to be nervous about flying when wrapped in this sound.

Brian Wilson at the San Diego Zoo, February 15th, 1966. (Photo by George Jerman).

Composed and produced by Brian Wilson and given life by the finest musicians of The Wrecking Crew, with this tune the warts and worries of whole world can simply soften into a realm of tranquil sound. For some reason or another, this song always brings to my mind the Jim Carroll poem, Fragment: Little N.Y. Ode, from his 1973 collection, Living at the Movies. This work too comes across as a satisfied sigh:

Jim Carroll, June 22nd, 1979 (Photo by Michael Zagaris)

I sleep on a tar roof.

scream my songs

into lazy floods of stars…

a white powder paddles through blood and heart

and

the sounds return

pure and easy…

Ah, this city is on my side.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[2) Sun King – The Beatles (1969)]

August 22, 1969, one month after recording “Sun King.” (photo by Ethan Russell and Monte Fresco).

Having received The Beatles Box Set as a Christmas gift from my wife, I flew to Uruguay with my brain fully saturated in what is truly some of the greatest music ever recorded. Here, sun-kissed and brylcreemed, we have one of John Lennon’s contributions to “the Long Medley” that concludes The Beatles’ final masterpiece, Abbey Road. It all feels so free and easy; its emphasis on breath and the simple pleasure that exists in the soft spaces in between perfectly captures a languid day in the seaside village of Punta del Diablo, located 185 miles east from the capital, Montevideo, and just under 27 miles from the Brazilian border.

Here on this mix I conclude the track with a jumble edit of Beatles’ scraps and others to break and segue…

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Entering a conceptual room by Uruguayan artist Luis Camnitzer (born 1937), on display at the Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales in Parque Rodó, Montevideo. Here every object that would appear within the room, such as the rug, the curtains, and even the branches of a tree one would see outside a window are all plainly labeled within the empty room for you to fill in. Silly, simple, and great, I think.

[3) Para Hacer Musica, Para Hacer – Miguel Y El Comite (1971)]

In 1969-1970, Miguel Livichich made his fame in Uruguay and throughout the rest of South America with the group El Sindykato (The Syndicate). However, by mid ’71, due to “differences” (primarily financial) Livichich left the group to quickly form another whose name held a certain allusion to the band he abandoned: El Comité (The Committee). Approaching the band Feeling Rock he made it immediately clear that he intended to be the leader:

“I told them, I want a band to join me, but we all work together […]

Accept, and we make a titanic effort. An aggressive launch. I do not

lie, in fifteen days we were recording the LP. It was pin, pin and we

were playing at all the dances. It was amazing working with Miguel

Y El Comité” (Lion Productions, 2011).

This new group consisted of Washington Pachetto on drums and percussion, dual guitars handled by Bengochea Piece and Jose Maria Sanguinetti, Gustavo Luján on bass, and Miguel Livichich himself as principal songwriter, lead vocalist, on guitar, and responsible for the congas—an essential element to the candombe beat (the traditional musical style of rhythm idiosyncratic to the Uruguayan region) which Miguel Y El Comité helped pioneer the fusion of with swinging pop and rock music fuzz. As with so many groups of this era, financial hardship, frustrated ambitions, and political persecution by a military dictatorship helped scatter and silence the band.

However, here is the opening track off their 1971 debut, in which they cut through the illusory fat of image and fads and declare what is and what is not necessary “to create music, to create…” (By the way, to my ears this stuff sounds like just about the best groove music that The Beastie Boys never got to lovingly crib).

You don’t have to go around in weird clothes

You don’t have to have Che’s books

You don’t have to have hair, or a beard

Nor smoke Ambientex

…To Create Music…

You must know an inverted chord

You must listen to a little John Sebastian

Do not sing in gringo, they don’t understand you

No matter how much you shout, shout, shout…

…To Create Music…To Create…

You don’t have to have thousand-dollar equipment

It’s your soul that must sound

What good is an imported guitar

If you don’t know what it is to tune it?

…To Create Music…To Create…

…To Create Music…To Create…

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

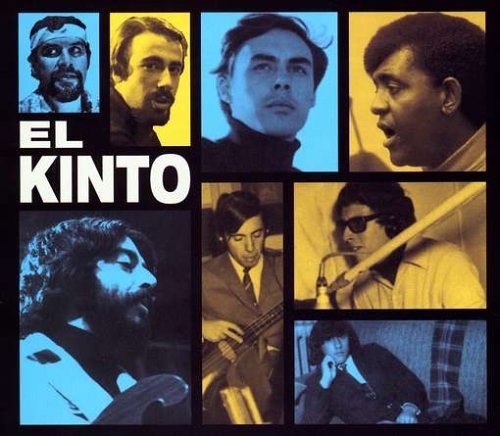

[4) Esa Tristeza – El Kinto (1968)]

Here we have one of the finest songs by one of the finest groups this world has ever known. While, as exceptional as they were, a band like Los Shakers may have received a reputation as “the Uruguayan Beatles,” this was due to their adoption and adhesion to an Anglo style. Meanwhile, it is El Kinto that truly deserves that moniker for their spirit of innovation and reinvention. As early as 1966, while most groups sang in English, they were insistent upon composing songs in their native castellano rioplatense Spanish (the variant dialect spoken mainly in the areas in and around the Río de la Plata basin of Argentina and Uruguay) and El Kinto were the first group to integrate Uruguay’s native music of candombe with psicodelic rock, pop, and bossa nova.

Economic yet strange in style, El Kinto consisted of two primary composers: percussionist and vocalist Rubén Rada (perhaps Uruguay’s most celebrated musician), and brilliant guitarist and vocalist Eduardo Mateo (perhaps Uruguay’s most celebrated iconoclastic madman). Despite some personnel changes the group featured the amazing talents of Walter Cambón on lead guitar, Urbano Moraes on bass and vocals, and Luis Sosa on drums. By 1969, after Rada and Moraes amicably left the group to pursue other opportunities they were replaced by virtuoso percussionist Mario “Chichito” Cabral and bassist Alfredo Vita. When the group completely disintegrated by the early part of 1970, despite being celebrated by the Uruguayan counterculture as a musical phenomenon, El Kinto had never actually recorded an album or even released a single other than as the backing musicians for a few pop acts. Oddly enough, all existing recordings of this group were quickly done so to play behind the group as they mimed a performance on the live, music television show Discodromo. Luckily, each appearance on the program allowed another opportunity to record, and so we have the roughly twenty tracks associated with the group today.

“Esa Tristeza” (That Sadness), a Eduardo Mateo composition sung by him and recorded in June of 1968, features such a peculiar, fluid shuffle that lilts along with some of the most poetically haunting lyrics I’ve ever heard:

That Sadness

That sadness that you have

Comes from a tired face

Comes from open hands

From hands that have escaped

From hands that have escaped

That sadness that hangs

Where your hair ends

Comes from a sea that has dried-up

While you dreamt desires

While you dreamt desires

You Think, You Go On And Think

I know very well what you have

There is in your life a past

Dust that the wind does not carry

Are your bad memories

Are your bad memories

You Think, You Go On And Think

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[5) No Puede Ser – Los Campos (1972)]

Los Campos – Naturaleza Viva (1972).

This lovely, harmony-driven slice of psyche-pop is the opening track to Los Campos’ (The Fields) second (and, unfortunately, last) LP: Naturaleza Viva. I believe the album’s title is supposed to be a play on words, but attempting to translate it hurts my head. Essentially, it is the opposite of a “still life,” as in a painting. The musicians (Julio César Arostegui on lead vocals and organ, Juan Gadea on lead guitar, Enrique Machado on rhythm guitar, Gustavo Musto on bass, and Pedro Robaina on drums) come together to create a seamless groove that is made all the more buoyant by the charming chant of the female vocal choir (Mariela Avellanal, Rosario Berro, Alicia Dandreis, and Silvia Richi).

The whirling tone of the Gadea composed “No Puede Ser” (It Cannot Be) works nicely against the distressed sentiment of the song—one likely shared by many South Americans (particularly artists and intellectuals) living under the austere depravity of a military dictatorship, where expatriation seemed to be the only viable solution to poverty, prison, or even death:

“No! I don’t want to go. I want to sing, in my country. It Cannot Be!”

Los Campos were rather successful, touring the whole interior of the country throughout 1972 with the full band, choir, light machines, and projectors (Peláez, 2004)—all culminating in a large year-end concert accompanied by a twenty-piece orchestra at Teatro Solis, Montevideo’s opera house (built in 1856 it is also Uruguay’s oldest theater).

In late 1973, however, in a story that is sadly repeated over and over with these bands, unable to sustain a career at home Los Campos traveled to Europe to perform in Spain, France, and Switzerland, but soon broke up in 1974.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

One of the pieces up for the DOGMA group show—featuring artists Javier Abreu, Julia Castagno, and Ernesto Rizzo—on display at the more subversive Subte museum, located underground, underneath the Plaza del Entrevero, on 18 de Julio Ave, Montevideo.

[6) Hermano Americano – Montevideo Blues (1972)]

Gastón “Dino” Ciarlo

Dino first came to prominence in the Uruguayan music scene as a DJ on Radio Ariel and with the beat group Los Gatos as well. On the weekends of his youth my father would attend dances where Dino served as the DJ, always spinning the latest in rock‘n’roll and candombe-beat. After a brief stint of releasing candombe-inflected pop singles himself and an LP as a solo artist in 1969 and the early 70’s, Dino was looking to abandon both his solo career and his legendary radio show La Tenaza (which tended to feature music by Bob Dylan, Cream, Ray Charles, and others like that). He knew that to accomplish the experimental musical ideas he had rolling around in his head for quite some time now he required a full band skilled in the diverse sounds of traditional Uruguay folk music. Dino searched for a band in order to “[…] fuse the rawness of rock music with obscure native rhythms like malambo, milonga and chamarritta […]” (Tornatore, 2007).

“The tropicalismo of Brazil made us realize that we had work

to do with our own national music traditions”

—Dino (Tornatore, 2007).

In 1972 he found just the group to accomplish this with—Montevideo Blues: Eduardo “Pocho” Díttamo (guitar and backing vocals); Néstor Barnada (guitar and backing vocals); Horacio “Niño” Costa (bass); Julio César “Lelo” Surraco (percussion); and José “Pepe” Martínez Díaz (drums). In addition to this “folk-rock” sound, this album features extremely incisive, political and socially conscious lyrics—particularly for a time when it was a true danger to do so. Like many at the time, Dino had been growing increasingly politicized, intensely so with his compositions. During his concerts of ’71 he would often pause in the middle of the show to read the Acts of Parliament, only to afterwards declare, “You realize that these guys are a bunch of liars!” (Tornatore, 2007).

Around this time—as the economy was collapsing, labor and student movements were holding demonstrations and strikes, and the left-wing urban guerilla group the Tupamaros were fighting the government in a struggle for equality and justice for the people—the government followed the example of so many other South American countries and declared a police state. In June 1968, President Jorge Pacheco, trying to suppress unrest, enforced a state of emergency and repealed all constitutional rights. The government began a program of imprisoning political dissidents (often secretly), used torture during interrogations, and brutally repressed demonstrations (Nahum, 1991).

Flag of the Tupamaros National Liberation Movement

By 1972 the majority of the Tupamaros had been either killed or were imprisoned under horrifying conditions where they would remain for well over a decade. In July of 1973, despite the deteriorated threat posed by the suppressed political dissidents, the government under Juan María Bordaberry dissolved parliament and ceded government authority over to the military, under whose auspices he remained as the first in a series of military approved presidents.

“President” Juan María Bordaberry

This bloodless coup led to further repression and the suppression of all political parties. The following month, the Tupamaros formed the Revolutionary Coordinating Junta with other leftwing groups pursuing urban guerrilla warfare in South America. This all soon led to Operation Condor, in which the military regimes in Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Brazil, and Bolivia all cooperated to repress, kidnap, torture, and kill intellectuals, socialists, and others deemed opponents. “Conservative estimates suggest a minimum of 60,000 people were ‘disappeared’ during Operation Condor […] and countless more were imprisoned and tortured” (Olle, 2012).

Upon their release from imprisonment after the collapse of the dictatorship in the late 80’s, many of the former guerrillas banded together to form a political party, which in recent years has won all of the elections and are now the progressive head of the Uruguayan Government. On March 1, 2010 former Tupamaro José “Pepe” Mujica—who spent 14 years in a military prison (two of those confined at the bottom of a well)—took office as President of Uruguay. On March 5th of 2010 former president Bordaberry was sentenced to 30 years in prison for his involvement in 1976 political assassinations. Prior to that, on October 22, 2009, another former Uruguayan president/dictator, Gregorio Conrado Álvarez was sentenced to 25 years in prison for 37 counts of murder and human rights violations (BBC, 2009).

President José “Pepe” Mujica

However, back in 1972 when Dino and Montevideo Blues were recording their sole album there was little hope in sight. Dino felt that this situation needed to be addressed in their music:

We follow the course of history, the history of those who suffer

from economic situations. And I say to you that I have been

hungry, and cold, and have had problems trying to buy a liter of

milk for my children. Yet the creators of the problems continue

to promise a better future: “within six months, we are going to see

an improvement,” “this year no, but next year yes, dear compatriots,”

and so on throughout history. The fault is always placed on the

international markets, and never on the bad economic conditions

that lead to social disasters; the blame is always placed upon

pensioners, teachers, health care workers, and of course, it is

always the fault of the left…When a musician or a composer

looks around and sees how his brothers live, he puts it in a song

—Dino (Tornatore, 2007).

Before Dino even commences with the declarative holler of his vocals “Hermano Americano” (American Brother) immediately demands the attention of your spinal column and shoulder muscles with its frenetic eddies of guitar that ripple around the percussive, clipped gallop of the rhythm and the corpulent bounds and burrows of the bass. This pace soon all give way to the weight of a rasped, surreal monologue over a jazz riff, wherein a child’s nightmare coalesces into the horror of bureaucracy and corruption that plague the world of adults. Another element of this song that I love is that it does not address the U.S. with blind ire, but with a moral superiority that serves to condemn and shame American arrogance. Here, Dino and Montevideo Blues wag their finger at the greasy muscle and appetite of the United States, and with good reason. All of the South American dictatorships were put into place not only with the U.S.’ support, but actual involvement.

Dan Mitrione

On July 31st of 1970 the Tupamaros kidnapped one Daniel A. Mitrione who had been serving under the Nixon administration as a United States government advisor for the Central Intelligence Agency in Uruguay. Mitrione, who was once quoted as having said, “The precise pain, in the precise place, in the precise amount, for the desired effect” (Patar, 2001) had been sent to Uruguay to instruct the police force there on effective torture techniques. It is said that “Mitrione had built a soundproofed room in the cellar of his house in Montevideo, in which he assembled selected Uruguayan police officers to observe torture-technique demonstrations” (Hevia Cosculluela, 1981). Allegedly, these demonstrations were conducted upon vagrants picked up off the street who were executed once the lesson was over. The Uruguayan government, with the United States backing, refused to meet the Tupamaros’ demands and Mitrione was later found dead in a car. Other than the two fatal gunshot wounds to his head, there was no other signs of maltreatment; he had not been tortured.

“Hermano Americano” (American Brother)

American Brother

American Brother, this is for you

American Brother

American brother, remember

That the owner of the world is not the strongest

But the one that is right

The pirates

Have a thousand frigates

Pointed sabers,

They always wear neckties,

They have hair on all their feet,

Heads of the dead,

and long hands.

The Pirates are all made of glass

And many get scared when

They talk of the town

Once they have retired

All they do

Is run for Deputy

American Brother

American Brother, this is for you

American Brother

American brother, remember

That the owner of the world is not the strongest

But the one that is right

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[7) And I Love Her – La Fragua (2001)] [Snippet]

Originally Released in June of ’64 as a 7” single.

Just a snippet of the Argentinean band La Fragua’s rendition of Paul McCartney’s beautifully stark opening phrase to The Beatles “And I Love Her.” While in our apartment in the Pocitos beach area of Montevideo (generously lent to us by my amazing aunt and uncle in Australia) I nearly immediately turned the dial to 97.1 and tuned in to discover the wonderful public radio station Babel, which plays classical, Jazz, and a vast array of “folk” music from around the world: everything from bossa nova to Tibetan throat singing! Babel remained the only stationed I listened to the entire time I was there in the capital, and one of the many groups it turned me on to was La Fragua.

Formed in Bariloche, which is situated in the foothills of the Andes on the southern shores of Nahuel Huapi Lake in Argentina, La Fragua perform remarkable covers of The Beatles tunes by incorporating the folkloric instrumentation and traditional styles of South America—here you can watch them perform a fun rendition of “Yellow Submarine” as a Chamamé (a sort of Argentinean Polka).

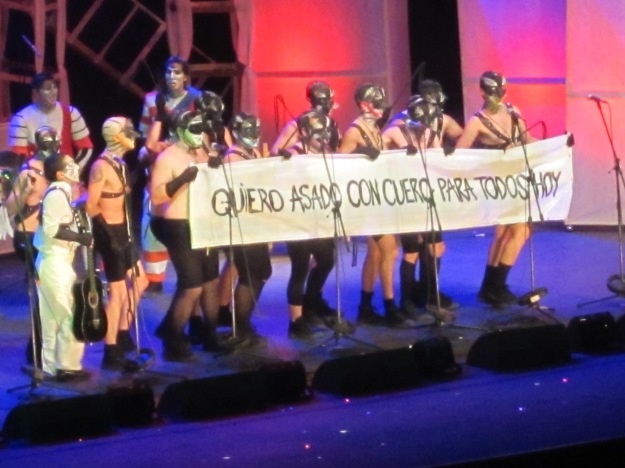

Anyway, the reason here for including only a snippet (other than time constraints) of “And I Love Her” is that this musical phrase was utilized during one of the more placid segments (of which there were very few) of the hilarious Murga we saw performed by the group La Leyenda (pictured above) at the Teatro De Verano, an outdoor amphitheater in which a major portion of the Carnaval concerts are held. A type of theatre, murga operates as a sort of “cultural therapy” in which competing groups prepare a 45-minute long musical play consisting of costume changes and a suite of songs that address (often hysterically) current events and “hot topics” in Uruguay or elsewhere over the preceding year, such as racism, the legalization of marijuana, gay-marriage, and reckless drivers (a true hazard in Montevideo).

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

“The legend of this young fountain tells us that if a lock with the initials of two people in love is placed in it, they will return together to the fountain and their love will be forever locked.”

[8) Valentine Day – Paul McCartney (1970)]

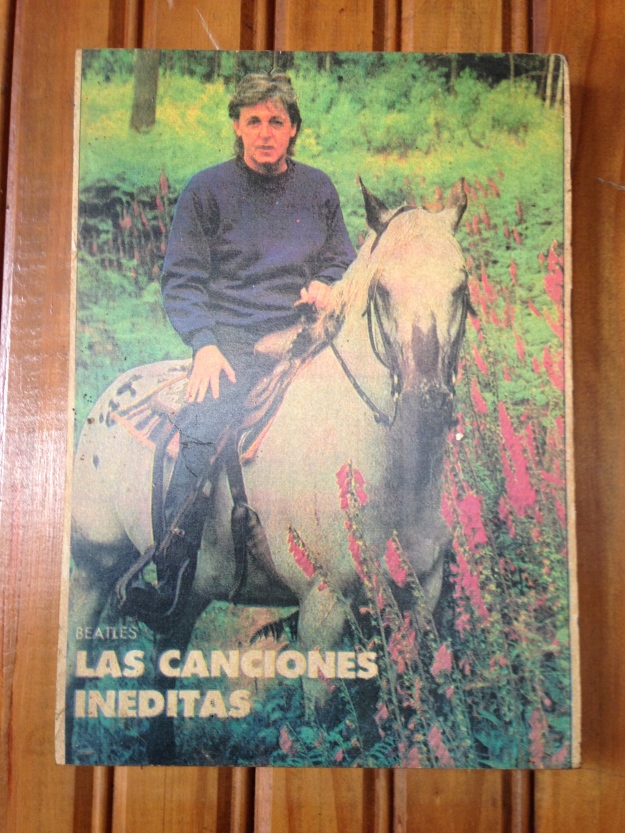

McCartney

After spending the live-long-day walking along the beach and through the town of Punta del Diablo, eating empanadas and fresh seafood, we spent the evening on our deck watching the shore, talking, and (accompanied by some Fernet Branca and liters of Cerveza Patricia) doing a little tipsy boogie-woogie to this and other numbers off of Paul McCartney’s solo debut, McCartney, released in April of 1970.

Playing every instrument himself (although his wife Linda does add the occasional backing vocal), McCartney’s impeccable knack for the interplay of rhythm with vertical melodies is here applied to a rough-recorded and ramshackle patchwork of pop, blues, rock & roll, country, funk, and folk. Odd, amusing, and never taking itself too seriously—this quick LP is a simple pleasure to listen to. Under appreciated—highly recommended.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

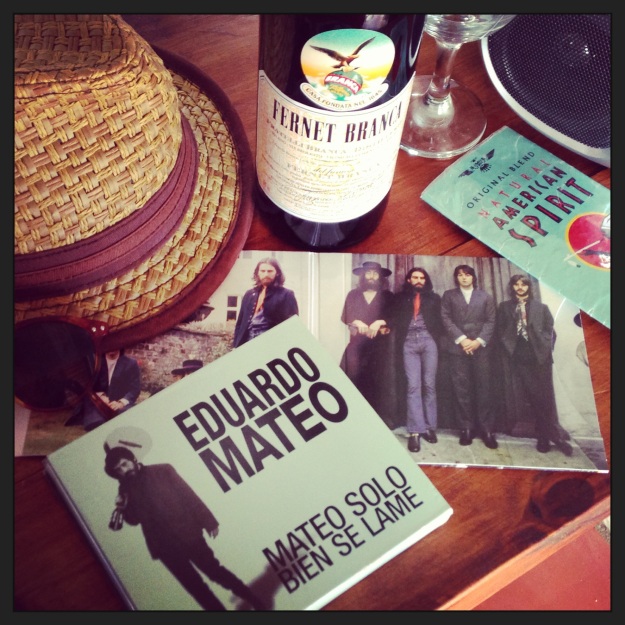

[9) Jacinta – Eduardo Mateo (1972)]

A sweet bossa nova by a pure musician. By the time El Kinto had officially disintegrated in the early part of 1970 most of Mateo’s friends and associates were already convinced that he had gone completely insane. Despite the fact that these same people viewed him as a musical genius, they did not know what to make of his habits of disappearing for days at a time, either to lock himself up somewhere in a rented room to explore new realms on his instrument while searching for spiritual enlightenment through chemicals, or to wander the streets with nothing but pajamas and a guitar—there was always a guitar, a rare constant in this man’s unhinged life. Once, my uncle saw him walking the streets at night with one foot aligned with the curb, the other with the gutter, so that he was forced to maintain an awkward and drastic limp to his gait—how’s that for a metaphor?!

Speaking of this period in Mateo’s life, Uruguayan singer Verónica Indart had this story to tell:

“The last time I saw him was in the first years of the 1970s. I was

with Héctor, my husband, and Mateo arrived. He entered, he took

up the guitar, and he sat down to play by the window, looking at the

sea for a long while. We listened to him. When he finished, he got up,

he set down the guitar and he went out the door without a greeting.

That was Mateo. He arrived, gave us his music and went on without

greeting us, because it was not necessary” (Lion Production, 2006).

In 1971, for those who were fortunate to have heard Mateo play there was no doubt of that man’s overwhelming talent—mental illness or not; however, beyond a handful of tracks there existed little recorded evidence of it. This would soon change due to the influence of talented singer Diane Denoir, and through the dedication and passion of producer Carlos Píriz. Píriz, a recording technician who had worked for the live, music television show Discodromo had recently started the record label De la Planta along with Jorge “Coyo” Abuchalja, guitarist for the group Los Delfines. The ethos behind this venture was to maintain a Uruguayan label that was dedicated to Uruguayan musicians, providing them with better production, recording techniques, and better distribution than the then norm. Fortunately, through Píriz’s connections, they were able to secure regular studio time at ION Studios in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where the recording technology was far superior to that found in their native country (four tracks as opposed to two at most, for example).

Diane Denoir

In October of 1971 one such artist they chose to present to the public was the singer Diane Denoir. As she was recording a fair amount of Mateo’s material for her De la Planta debut, she felt it was only appropriate that the artist himself accompany her on some of the tracks. Having convinced Mateo to take the trip, Píriz quickly took advantage of the rare opportunity by persuading him to stay and record a solo LP for the label. However, in spite of Píriz’s optimistic plans to complete the recording in one week, he soon found that dealing with this erratic artist would be an ultimate test of endurance and patience.

The sessions went like this: Mateo had an alphabetic notebook,

and stuck in each page he had bar napkins upon which his songs

were written. If he knew the first letter of the title of the song he

wished to play, he would find the correct napkin, which would help

him remember the melody, so that he could recreate the original idea

he had envisioned when he had composed the song in the first place.

Remembering the songs was only the first obstacle […]. Mateo

would record songs one day, and erase them the next. “The first day

he recorded three or four things,” Píriz recalled. “The following day

he came in and said, ‘erase them. For Mateo, they are all wrong.’

We erased them. And that process of erasing the previous day’s work

continued for four or five days. At that moment, I understood that this

would be the system for the whole disc […]. I decided that I will be the

person who says what was well-recorded, or not, and I began to keep

all the material.”

On other days, Mateo went to ION studios only to say that he was not

inspired, and would return the next day. Then there were the days that

he appeared at the studio, and asked, “What time do we record tomorrow?”

“The same as today, at four o’clock,” Píriz would say. “Okay I am going,

until tomorrow,” was Mateo’s only reply (Lion Production, 2006).

This whole arduous process continued for two months, until one day when Mateo said to the producer that he was stepping out of the studio to buy a pack of cigarettes, and never came back. He had returned to his streets in Montevideo. Píriz was left holding hours of recordings of these fragmented sessions—the only proof that Mateo had even been there. A labor of love, Píriz would then spend the better part of a year assembling these into the album that would be released in December of 1972: Mateo Solo Bien Se Lame.

One of the thirteen brilliant compositions that Píriz extracted from the chaos is the lovelorn “Jacinta.” Through his dedication, Píriz was able to capture on this record the complex sensitivity of this troubled artist. Seeing as how, other than a rare background vocal here and there, Mateo created every sound on this album himself, his essence truly shines through each composition. I particularly love the closing movements to this track, when the song suddenly shifts to a delicate chooga-chooga as the singer warns: “Hurry, the train is leaving.”

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[10) Fields Of Joy – Lenny Kravitz (1991)]

Each bus in the capital city of Montevideo tends to have some idiosyncratic feature, some personal touch that distinguishes it from others. This fact, coupled with their apparent cleanliness (you can typically find a bucket filled with cleaning supplies stuffed under one of the seats) led my wife and I to believe that each driver might actually own the bus he drives. In addition to the personal touches—such as a neon peace sign or a John Lennon poster—the drivers tend to play their own radio over the loudspeaker system. On one particular ride we took from the neighborhood of Pocitos to Ciudad Vieja the driver was rocking Lenny Kravitz’s sophomore album, Mama Said, released in April of 1991.

As this is the only Kravitz album that could accurately be described as brilliant (believe me, I own a good deal of them), and seeing as how I haven’t listened to it in about a decade—I was truly enjoying this ride: The bright, hot light of the sun piercing through the blue curtains while over the rumble of the engine the opening notes of acoustic guitar walk calmly alongside the slow psychedelic trill of a mellotron, falsetto vocals— “…All trouble slowly fades away…”—all mounting to an outburst of rock ‘n’ roll cut and crunch. Taut and diverse, on his follow up to his 1989 debut, Let Love Rule, Kravitz develops the catchiest elements of his influences (the obvious ones being Hendrix, Lennon, Sly Stone, Prince, and Al Green) but elevates what could have been mere revivalism and kitsch by focusing them through the various, fervent emotions and anguish churned up by the impending end of his marriage to actress Lisa Bonet, mother to his two-year-old daughter, Zoe.

Kravitz & Lisa Bonet with their daughter Zoe.

Kravitz & Slash

Impressively, Kravitz essentially functions as a one-man-band here on this album, playing nearly every instrument and even creating the horn and string arrangements. Opening track “Fields of Joy” is one of the rare exceptions, featuring the soaring, keen-edged and held bends of Slash’s guitar playing. “Fields of Joy” is also a rather peculiar choice to open the LP with, as it is a cover of a little remember group, The New York Rock Ensemble, who first released the song on their 1971 album Roll Over. This song in particular was co-written by the group’s organ and oboe player Michael Kamen who would go on to find fame as a composer for films such as Lethal Weapon, and the Die Hard movies. Another member of the group, Martin Fulterman, would later be known as Mark Snow, creating the theme music for several sci-fi television series such as The X-Files and Smallville. I wont go into what I believe went wrong with Kravitz, but I am sure that more than one of you must have rolled your eyes upon seeing his name. Swallowed whole by the cartoon menace of image and frivolous fads, I assure you that at one point he was fairly consistently recording some solid tunes.

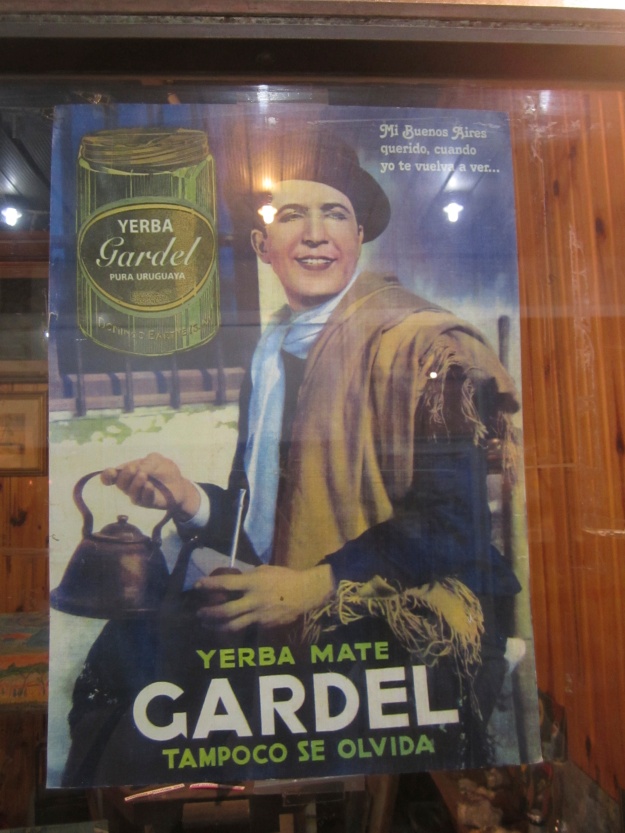

This song certainly popped up in my head more than once while roaming on horseback, rounding up cattle and sheep on roughly 2,400 acres of land at the estancia, Panagea; a gaucho ranch located about an hour outside of Tacuarembó in the far north-central region of Uruguay (it is this area that Uruguayans believe was the birthplace to the world’s most celebrated figure of Tango, Carlos Gardel, an assertion that is still hotly contested by both France and Argentina, who both lay claim to him as a national son).

An old advertisement for yerba mate on display in one of those odd, dusty galerías that run through the blocks surrounding the avenue 18 De Julio in the Centro area of Montevideo.

Panagea is certainly one of the greatest places to be found on this green earth:

“I was told when I grew up I could be anything I wanted: a fireman, a policeman, a doctor – even president, it seemed. And for the first time in the history of mankind, something new, called an astronaut. But like so many kids brought up on a steady diet of westerns, I always wanted to be the avenging cowboy hero – that lone voice in the wilderness, fighting corruption and evil wherever I found it, and standing for freedom, truth, and justice. And in my heart of hearts I still track the remnants of that dream wherever I go, in my endless ride into the setting sun.” – Bill Hicks

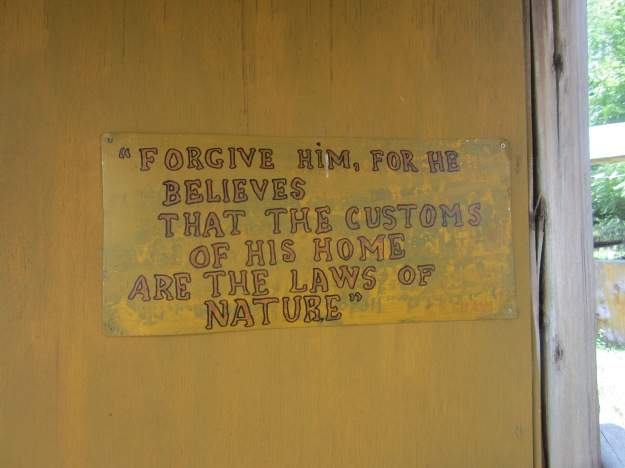

Owned and operated by Juan and his wife Suzanna—who together are a splendid combination of culture, dry-humor, and convivial conversation—this ranch offers one some first-hand (albeit clumsy hands in my case) experience of the no-frills yet pure-joy of the Gaucho culture. I implore all who read this to make an effort to visit this place and stay in their grand (albeit without electricity) home. It was here at Panagea that I also encountered this bit of wisdom, hand painted on a sheet of wood:

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[11) La Conferencia Secreta del Toto’s Bar/Mi Tía Clementina – Los Shakers (1968)]

The phenomenal, Uruguayan musical siblings, the Fattoruso brothers (Hugo and Jorge Osvaldo), got their start as children playing in a jazz trio with their father. In 1964, however, upon hearing the music of The Beatles the brothers decided that this model was the direction they needed to take their music and image, and enlisted bassist Roberto “Pelin” Capobianco, and drummer Carlos “Caio” Vila to create Los Shakers. Singing original composition written in English, they developed into a pop-rock sensation that, like basically every other band in existence in the 60s, would follow the new musical leads established by each subsequent release by “The Fab Four.”

By 1968, as Osvaldo Fattoruso would later note, the band was “tired of playing at being the Beatles” (Zolov, 2011) and soon went their separate ways. “[Los Shakers’] dissolution marked the end of an era in which, for a brief period, English-language Uruguayan rock dominated the South American pop charts” (Zolov, 2011). However, they would first release their attempt, ala Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, at a psychedelic masterpiece: La Conferencia Secreta del Toto’s Bar (The Toto’s Bar’s Secret Conference). During the recording of the album the group had already determined to dissolve, and thus abandoning commercial aspirations, they diversified their sound and added native rhythms to create a more original, organic musical sensibility modeled after the “strange” liberation of form The Beatles had demonstrated. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band had as great an impact on Latin American culture as it did throughout the rest of the world. As Ian MacDonald wrote in his exceptional track-by-track assessment of The Beatles’ output, Revolution In The Head:

When Sgt. Pepper was released in June [of 1967], it was a

major cultural event. Young and old alike were entranced. […]

In America normal radio-play was virtually suspended for

several days, only tracks from Sgt. Pepper being played. An

almost religious awe surrounded the LP. Paul Kantner of the

San Francisco acid rock band Jefferson Airplane remembers

how The Byrds’ David Crosby brought a tape of Sgt. Pepper

to their Seattle hotel and played it all night in the lobby with a

hundred young fans listening quietly on the stairs, as if rapt by a

spiritual experience. “Something,” says Kantner, “enveloped the

whole world at that time and it just exploded into a renaissance.”

The psychic shiver which Sgt. Pepper sent through the

world was nothing less than a cinematic dissolve from one

Zeitgeist to another. In The Times, Kenneth Tynan called it

“a decisive moment in the history of Western civilization,” a

remark now laughed at but nonetheless true, if perhaps not quite

in the way that it was intended. As the shock wore off, voices

from an earlier age began to complain that this music was

absolutely saturated in drugs. Not wishing to promote LSD,

the BBC banned “A Day In The Life” and “Lucy In The Sky

With Diamonds,” while others found drug references inn

“Fixing A Hole” and “With A Little Help From My Friends.”

More Bizarrely, “She’s Leaving Home” was attacked by

religious groups in America as a cryptic advertisement for

abortion.

While half these claims were spurious, it would be silly

to pretend that Sgt. Pepper wasn’t fundamentally shaped by LSD.

The Album’s sound—in particular its use of various forms of echo

and reverb—remains the most authentic aural simulation of the

psychedelic experience ever created. At the same time, something

else dwells in it: a distillation of the spirit of 1967 as it was felt by

vast numbers across the Western world who had never taken drugs in

their lives. If such a thing as a cultural “contact high” is possible, it

happened here. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band may not have

created the psychic atmosphere of the time but, as a near-perfect

reflection of it, this famous record magnified and radiated it around

the world (2007).

It’s easy to write-off La Conferencia Secreta del Toto’s Bar as a “Sgt. Pepper” rip-off but I could rattle off the top of my head a dozen renowned groups (The Rolling Stones, for one) that did the same, only not as convincingly or inventively as Los Shakers.

Che Guevara visiting with Uruguayan President Eduardo Victor Haedo at Haedo’s summer home in Punta del Este, Uruguay, Aug. 7, 1961. Che was sent to head Cuba’s delegation to the economic conference of the Organization of the Amercian States (OAS) at Punta del Este, Uruguay, where he denounced U.S. President Kennedy’s “Alliance for Progress.” (Click here to read the remarkably audacious, yet earnest speech that Che delivered on August 8, 1961 at Punta del Este: http://www.marxists.org/archive/guevara/1961/08/08.htm

Recorded shortly after the assassination of Argentine guerrilla revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara by Bolivian special forces trained, supported, and orchestrated by the CIA, the title track, “La Conferencia Secreta del Toto’s Bar”—which segues directly into the amusing, listless and ragged jazz waltz of “Mi Tía Clementina” (My Aunt Clementine)—is “a sardonic retelling of the [January 31] 1962 meeting [in Punta del Este, Uruguay] that led to the expulsion of Cuba from the Organization of American States” (Zolov, 2011). Despite being a founding member of the OAS, following the Cuban Revolution of 1959 The United States had encouraged OAS representatives from South and Central America as well as the Caribbean country of Haiti to advocate a hard line against Cuba, which would eventually see Cuba suspended, denied the right of representation and attendance at meetings, and of any participation in activities.

“Maybe I read it in a storybook/Maybe in a picture/beneath the author’s desk/There were three generals with little boots/Each one with a pocketful of medals/ […] /From London, Paris, Berlin, they went on holidays/They billed the kids from Uruguay/And stopped at San Rafael” —(San Rafael being a very popular hotel/casino in Punta del Este, which on February 18, 1969 would be robbed by members of the Tupamaros for a total of 70 million pesos).

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[12) African Bird – Opa (1976)]

Opa: the Fattoruso brothers & Ringo Thielman

To demonstrate the sheer virtuosity of the Fattoruso brothers—soon after the dissolution of Los Shakers they moved to New York City and formed the latin-jazz fusion group Opa: featuring Osvaldo now on drums, percussion, and vocals; Hugo now handling vocals and keyboards; and Ringo Thielman on bass and vocals. Through their concerts during the early 1970s this exceptionally innovative trio caught the ear of Brazilian percussionist extraordinaire Airto Moreira (who helped color and create the sessions surrounding Miles Davis’ genius work on Bitches Brew, which was already featured in these pages, here—.

Airto Moreira

Airto was so impressed with the fluid, musical camaraderie of Opa that he employed the group (along with his own wife, vocalist Flora purim, and guitarist David Amaro) to function as the band for his stunning 1973 LP Fingers.

Fingers line-up: Flora Purim, David Amaro, Airto Moreira, Hugo Fattoruso, and “Jorge” osvaldo

Essentially utilizing the same musical configuration (but adding Hermeto Pascoal on flute), Airto would then go on to produce and contribute to Opa’s only two LPs, 1976’s Golden Wings, and Magic Time, released in 1977.

A Rubén Rada composition recorded for Golden Wings (Rada himself would become a member of the group for their second LP), the sound of “African Bird” perfectly hints at the sensation of standing amongst the crowds on the street Isla de Flores, while watching the participants in the Llamadas parade their way through the neighborhoods of Barrio Sur and Palermo: the intricate rhythms of hundreds and hundreds of drummers marching while mammoth flags and banners pass over the throng of brightly costumed and bare-skinned dancers.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The wife and I at Panagea helping Juan Manuel and Balinga corral innumerable sheep and cattle so that they could receive their vaccines and treatment for hoof rot:

Two works from the Pareja series (or Cosmic Couple series) by Uruguayan painter, potter, musician and key figure in the Constructivism Art movement: José Gurvich (January 5, 1927 – June 24, 1974).

————-

Sitting in the sunshine along Montevideo’s Rambla:

[13) Barnyard/Old Master Painter/You Are My Sunshine – Brian Wilson (2004)]

It is generally understood that The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper was in part created in reaction to The Beach Boys’ brilliant and Brian Wilson directed LP Pet Sounds. In 1967, while deeply entrenched in an attempt to create an ambitious follow-up to that work, a 24-year-old Brian Wilson would suffer a severe and complete mental breakdown. This, along with conflict within the group would force them to abandon the project that Wilson had collaboratively conceived with lyricist Van Dyke Parks: SMiLE.

Wilson while recording the track “The Elements: Fire (Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow).”

Despite being envisaged as a “benchmark in the use of the studio as the ultimate instrument, […] the next step in the evolution of record production” (Leaf, 1990), in September of 1967 the world received in its stead the rerecorded scraps, Smiley Smile. While wholly enjoyable (and at times brilliantly weird) it is hard to disagree with Carl Wilson’s assessment of the album as “a bunt instead of a grand slam” (Carlin, 2006).

Astonishingly—thirty-six years after the project was aborted and after decades of arduous mental rehabilitation—in 2003 Wilson (along with Parks and Darian Sahanaja, keyboardist and backing vocalist in Wilson’s touring band, The Wondermints) decided to take on the daunting task of revisiting and completely rerecording the entire conceived album from memory!

Turn that frown upside down

The trio made subtle changes to the music when necessary,

and in the spring, Wilson headed to Studio One at Sunset

Sound in Los Angeles to make his record. Just as he’d made

the original “Good Vibrations” and “Heroes & Villains” there,

Wilson gathered his band, strings and brass to record the tracks,

cutting the basic arrangements live while doing the vocals on

the same tube consoles his old Beach Boys had (Leone, 2004).

The results, released in 2004 as Brian Wilson Presents Smile, is a stunning, intricate suite of songs that create a musical journey across a conceptual America, from east to west: beginning at Plymouth Rock and ending in Hawaii. Although exceedingly delayed, it certainly lives up to what Wilson ambitiously described in 1966 as “a teenage symphony to God” (Richardson, 2011). Perhaps weird on my part, but one of my favorite sections of this album has always been when the melodic cacophony of “Barnyard” thumps, plucks, and sways into a glum rendition of the American standard “You Are My Sunshine.”

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Some shots from the elaborate musical Mi Morena performed at the Teatro de Verano for the Carnaval season of 2013:

[14) Principe Azul – El Kinto (1968)]

Oscar Wilde in 1882 (photo by Napoleon Sarony).

Yes: I am a dreamer. For a dreamer is one who can only

find his way by moonlight, and his punishment is that he

sees the dawn before the rest of the world.

― Oscar Wilde, in The Critic as Artist (1891).

Another remarkable track from El Kinto in 1968; the at-times lugubrious but always tender lullaby “Principe Azul” (Blue Prince), about one boy’s desire to enter his dream and stay there. The song was musically composed by Eduardo Mateo, while the lyrics were the work of actor and theater director, Horacio “Corto” Buscaglia. In 1969, these two would go on to create and direct the Musicasiónes, a series of four live concerts fundamental to Uruguayan popular music held between June and November at the Teatro El Galpón in Montevideo.

By 1969, El Kinto had great prestige among counter-cultural

young people in Uruguay, people described as having “an

expansive mentality characteristic of the Woodstock era and of

the hippie movement.” All the band needed was someplace to

play on a regular basis, a way to establish themselves in a relaxed

setting (perhaps harkening back to those days in Orfeo Negro).

Theater El Galpón came to the rescue […]. El Kinto was the host

group [for the Musicasiónes], assisted by a myriad of guests who

made renaissance music, danced tango, recited poetry, or played

music: jazz, bossa nova, candombe, free improvisations in support

of movies that were projected on stage, as well as other music best

described as indefinable. There were slides, sketches, dances, and

creative light effects, all obtained with negligible economic

resources, and realized without rehearsals (Lion Productions, 2006).

“Principe Azul”

Eduardo Mateo -vocal, rhythm guitar

Urbano Moraes – keyboard, bass

Walter Cambón – lead guitar

Luis Sosa – drums

“Chichito” Cabral & Rubén Rada – percussion

—————————–

Dream, Blue Prince.

Little child you are.

You’ll have moons of cheese.

Where will the moon go?

It strikes twelve and you’ll have

Little glass slippers.

Blue Prince, you’ll have them soon,

Little mice will bring them.

When you wake from your dream

The sky will no longer have the moon.

You should look for that kiss.

Better follow your dream.

You’ll have an enchanted forest.

Alongside the drumming rabbit,

White squirrels will come.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[15) Fly – Nick Drake (1970)]

Waking up feeling a little worse for wear in our little beach-side apartment in Punta del Diablo, and after procuring a large cup of coffee (not an easy task in Uruguay, I had to convince the woman behind the counter at a small beach-side bakery to dump the remnants of the pot into a plastic container she happened to have on hand as opposed to only selling me a tiny paper cupful), I believed Nick Drake’s album of 1970—Bryter Layter—would be the perfect thing to ease into the bright day with. The second of the trio of LPs he recorded before his death on November 25, 1974 from an overdose of antidepressants, this has always been my favorite of Drake’s albums. Here, Nick Drake’s ethereal yet morose melodies, and introspective, poetic lyrics are granted a Baroque elegance through the production work of Joe Boyd and arranger Robert Kirby’s undulating orchestration. The end result is a work that is captivating without being obtrusive, something that holds the weight of “art” but is still pleasant to listen to.

As the album played I sat in the sun to drink coffee mixed with chocolate milk poured from a plastic bag and read Voice Of The Fire, the spellbinding debut novel by celebrated comic book writer Alan Moore. Released in 1996, the novel takes place in the month of November but over a period of 6,000 years and follows the lives of twelve people who lived in the same area of England (Moore’s hometown of Northampton). In a twist of metafiction with the last chapter, Moore describes the work with these words:

It’s about the vital message that the stiff lips of decapitated

men still shape; the testament of black and spectral dogs

written in piss across our bad dreams. It’s about raising the

dead to tell us what they know. It is a bridge, a crossing-point,

a worn spot in the curtain between our world and the

underworld, between the mortar and the myth, fact and fiction,

a threadbare gauze no thicker than a page. It’s about the

powerful glossolalia of witches and their magical revision of

the texts we live in. None of this is speakable.

Unfortunately, with more-or-less a hundred pages to go, I would go on to lose the book while staying at the Panagea ranch; even still—highly recommended.

Perhaps in a couple of decades Juan and Suzanna’s adorable daughters, Dharma and Abril, will enjoy the book?

Anyway, as the seventh track “Fly” swelled and chimed with John Cale’s moaning viola and ornate harpsichord, my wife began to stir from her sleep in the upstairs bedroom. Through that initial gauze of first opening your eyes to a hangover she heard Drake’s repetitive whine of Please and believed that there was a diminutive cop at the door squeaking out “Police!…Police!” A slight, sluggish, yet amusing panic momentarily followed.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The 246 ft. tall tower and tomb of aviator and pioneer Aaron De Anchorena (November 5, 1877—February 24, 1965), set on his ranch where the left bank of the San Juan River flows into the Rio de la Plata. Upon his death he donated all 1,370 acres of this arboretum and wildlife conservatory to the state to serve as both an educational park and as the retreat home of the president.

[17) Hombre – Eduardo Mateo & Verónica Indart (1969)]

Eduardo Mateo (1940–1990).

In 1967, just as El Kinto were commencing their brief but significant career built from the remnants of the band Los Malditos, Eduardo Mateo met singer Verónica Indart and life-long friend Horacio Buscaglia. By 1969 El Kinto began to dissolve, in part due to Mateo’s erratic behavior, “his drug use, his anguished search for a transcendental spiritual dimension, his intransigence and pursuit of full authenticity” (Lion Production, 2006).

As singer Vera Sienra (with whom Mateo worked with on her lovely and delicate debut LP Nuestra Soledad) said of him at this time in the musician’s life:

Mateo was always strange, an almost unreal man in

many aspects. He could be very aggressive, very violent,

but he also was an extremely timid man, very spiritual,

with a great tenderness. His ambitions were creative. He

put all his genius, all his effort, all his pride there, while

others were suddenly looking for ways out of Uruguay.

Suddenly, Mateo was like a hermit…he had moments

when he communicated in monosyllables. You had to

interpret it. It was almost a conversation in key

(Lion Production, 2006).

Throughout the years of 1968 and 1969 Mateo spent long stretches of time living at the home of Buscaglia’s parents in the Montevideo neighborhood of Malvín, and from this intimacy the pair would enter a creative partnership that would produce, among other things, the beautiful song “Principe Azul” and the Musicasiónes series of concerts as well. In 1969, as the two became absolutely enamored by the traditional ethnic music of the Orient—particularly Hindu—they embarked on what would be one Mateo’s numerous unfinished projects. Intended to be one of the first productions released by the newly formed De la Planta label—beyond selecting the title of Horama, they never got further than recording three songs: “Hombre,” “Mumi,” and “Margaritas Rojas.”

The hypnotic dirge of “Hombre” features Verónica Indart’s vocals, which despite their cold drone are imbued with a certain empathetic charisma, which similar singer Nico of The Velvet Underground could never quite seem to fully get across for me. The whole enchantment is completed by Federico García Vigil’s work on double-bass, while Mateo provides both the percussion—emulating the timbre of tablas despite being played on bongos—as well as byzantine acoustic guitar, in which one feels they could wander for hours and never find an exit.

“Hombre” (Man)

While the man sings

Kills

Lives

Man

Time makes the boy

Something

Cries

Man

Joins his hands

Calls shouting

Man, Man, Man

Where the people pass by

Dreams

Run

Man

A far caress

Groans

Sorrow

Man

Joins his hands

Calls shouting

Man, Man, Man

Man

Only

Man

Man

Man

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

My wife assimilating into the ubiquitous culture of bitter yerba mate at my aunt’s house in the Prado neighborhood of Montevideo, where my mother was born and where all my family there now lives.

[18) Norwegian Wood (Baguala) – La Fragua (2001)]

Here we have a full performance by the wonderful group whose music I was introduced to though Montevideo’s remarkable radio station Babel: La Fragua. Over the course of two albums thus far La Fragua perform renditions of The Beatles tunes by incorporating the folkloric instrumentation and traditional styles of South America into their covers. Taken from volume I of their De Los Andes a Los Beatles series, they creatively reconceptualize the Lennon-McCartney penned classic “Norwegian Wood” as a baguala. The baguala—being a unique folkloric genre native of northwestern Argentina where the valleys extend from the Tucumán province to the border of Bolivia—descended from the mixture of Spanish Colonials with the indigenous communities of the Diaguitas and Calchaquíes peoples. Clever and celebratory throughout, La Fragua demonstrate their brilliant talent for arrangement with the subtle but startling fade-out made here by transitioning from a mesh of festive, adenoidal chanting and crystal guitars to the somnambulated twinkle of the descending chromatic bass line from “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.”

Released on the brilliant Rubber Soul LP in December of 1965, “Norwegian Wood”—made indelible in popular memory by George Harrison’s innovative use of a sitar to double the main descending line—was begun by Lennon during January-February of 1965 while on a skiing holiday in St. Moritz, Switzerland. Lennon’s elusive narrative is now generally recognized as a confession to his wife of an affair, however, at the time it was truly the product of The Beatles attempting to break new lyrical ground; particularly in the wake left by Bob Dylan’s stunning singles from earlier that same year: “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” As Ian MacDonald writes, Lennon was quite aware of the inspirational debt he owed Dylan and actually grew to be quite troubled by what might be the songwriter’s reaction:

For his part, Lennon was uneasy about trespassing on Dylan’s

territory and when the latter, on his next album Blonde On

Blonde, produced an inscrutable parody of Norwegian Wood

called “4th Time Around,” the head Beatle was, as he later

admitted, “paranoid”: what did the title mean? Norwegian

Wood, I’m A Loser, You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away,

and…Baby’s In Black? Or was it the [peaked “Dylan”] cap

[Lennon wore]? And what was Dylan driving at in those closing

lines: “I never asked for your crutch/Now don’t ask for mine”…?

In the end, the matter was settled amicably when the two met—

for the fifth time—in London in April 1966. In truth, Dylan got

on reasonably well with Lennon, with whom he had a fair amount

in common (2007).

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[19) 4th Time Around – Bob Dylan (1966)]

Dylan on Jacob Street in lower Manhattan in 1966 (photo by Jerry Schatzberg).

A few drinks into an evening in our rented apartment in Punta Del Diablo, I recall listening to Bob Dylan’s double LP and masterpiece of 1966, Blonde on Blonde, and attempting to explain to my wife why “4th Time Around” is one of the greatest songs of all time and how it features one of the most captivating narrative structures ever attempted by a popular recording artist. While I might not recollect all that I said, I stand by those statements. One thing that has always fascinated me about this track is how simply, logically, and direct the unexpected turn in narrative is designed; particularly so on an album comprised of, albeit genius, but often oblique verse ingeniously stitched to free-floating phrases from, as Greil Marcus has expressed it, “The Old, Weird America.” Here, Dylan once more demonstrates how he is a true artist of the songwriting form.

During those years, with the daunting amount of brilliant material he produced, Dylan must have worked on his craft constantly.

With all of its miscommunication, jilted feelings, occasional hysterics, postures, one-liners, and silly rapport (as if Lewis Carroll and Groucho Marx had both just watched Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell brilliantly bounce off each other in Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday and got the idea that they should team-up to write the details of a tryst at its end), the moment that it is realized that the entire jumbled affair of an afternoon in a woman’s house has not been confided to you, the listener, but to the woman who is featured in a photograph seated in a wheelchair, a woman that he immediately paid a visit to after the conclusion of the related events—this moment elevates the entire song into a complex emotional and intellectual spectrum of interpersonal relationships rarely ever touched upon so elegantly before or since the day this song was recorded down in Nashville on February 14, 1966 by a twenty-four-year-old Dylan. To add yet another layer to this impressive narrative, the tale is not being told to this woman on the day that these events occurred, but in some distant present. Much like the circular tune from which this takes its inspiration—The Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood”—the song operates as a confession of an indiscretion. It is the narrator coming clean and giving a complete account of what transpired that day he showed up on her doorstep with a shoe full of Jamaican Rum. However, this confession concludes with something other than a sentiment of remorse; it is more of a succinct summation of the dynamic of their particular relationship. It might be cold, but it is certainly not unfeeling:

And you, you took me in,

You loved me then,

You never wasted time.

And I, I never took much,

I never asked for your crutch,

Now don’t ask for mine.

The inside gatefold art for the first pressing of Blonde on Blonde, released May 16, 1966

Furthermore, it has always impressed me with what precision of language and time these narrative feats are accomplished. After all, it is still only a song, and one with the duration of just four minutes and thirty-five seconds. Other than perhaps a character or two’s affection, nothing here is wasted. With the economic exactitude of clockwork and the finest art the whirl of relatively candid words, delivered with cartoon dust in the throat, juvenile whimsy in the sinuses, and his flawless sense of emphasis are perfectly synchronized to an “archaic waltz” (Heylin, 2009) that is taken at a fast clip and put through its paces by the expert Nashville session men (such as Charlie McCoy, Kenneth Buttrey, and Joe South) Dylan employed to help him capture “that thin, that wild mercury sound” as he later described of the album in an interview with Ron Rosenbaum for Playboy in 1978.

Although both women featured in this tale might disagree, you the listener arrive at the final spirals of the song feeling much like the narrator: that there is nothing more that need be said. At a press conference given in San Francisco in December of 1965 Dylan stated, “All my songs basically say is Good luck. They all tail off at the end with good luck, hope you make it” (Gleason, 2006). With its final words spoken, with its final go-rounds of the spindly tune accompanied by the rapid tapping of percussion and harmonica trailing, it’s as if the narrator is walking off with an awkward smile that suggests: Hey, what more do you want from me?

Feb. 1966

Admittedly, I am a Dylan fanatic, but how can you not marvel at the mind that can create such things?

As an obvious nod to the iconic image of the songwriter by Milton Glaser, this photo illustration by Andrew Nimmo and Beth Bartholomew was created to accompany Duff McDonald‘s article, “Inside Dylan’s Brain,” published on April 8, 2008, in Vanity Fair.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[20) Zamba De Mi Esperanza – Jorge Cafrune & Los Chalchaleros (1964/2000)]

One evening in Montevideo we went out to catch a tango or two at Baar Fun Fun (pronounced foon–foon if you don’t want to receive a searching stare of incomprehension from a cabdriver). Founded in 1895, the club’s close quarters are comfortably comprised of old wood, a small stage, and walls cluttered with pictures of national icons of tango such as Carlos Gardel and festooned with brightly colored soccer jerseys and other bric-a-brac.

The space might be tight at times, but like true Uruguayans they don’t seem to fret too much:

I don’t recall the performers’ names that evening, but as my wife and I sat at a small table on the open-aired deck drinking Tannat wine as well as a small glass of sweet Uvita, we were treated to quite a show. A slick and taut couple rhythmically kicked, swiveled their torsos, twirled and stepped seductively to the evocative sounds of a bandoneón, all within the blue glow of a spotlight that cut through the dim room from above. At one point the man in the dark suit paused to posture and comb back his polished black hair while the woman wrapped tight in a red dress pumped her muscular thighs and sent the sharp heel of her shoe flitting past the eyes of the audience seated before her. It was a pleasure to watch something so controlled that yet suggested nothing but abandon.

This couple would alternate stage time with a small, older man with a great big voice who would accompany himself on acoustic guitar. Despite the fact that this man must’ve been only in his early sixties he would begin each love-sick tune with something like: Whoo, che, it must be fifty or sixty years since I’ve sung this one, so forgive me if I don’t recall all the words. This performer would then proceed to deliver the proper compound of stentorian command and injured drag that these types of songs demand—these songs that are so often the beautifully captured expression of men struggling to retain the will to live within the annihilation of love. After one of these amusing preambles the performer struck a familiar sputter and slope across his guitar strings and I immediately recalled hot summer afternoons of my youth spent at my grandmother’s: me, reading some Dungeons & Dragons type fantasy novel, listening through the ratcheting of cicadas to hear her sing along while tending her garden, or otherwise in the kitchen preparing a fine meal.

Written by Luis Profili in 1950, “Zamba De Mi Esperanza” (Zamba Of My Hope) gained widespread popularity when it was featured on the 1964 LP Emoción, Canto y Guitarra by Argentine folk singer Jorge Cafrune, becoming something of a Latin American standard (it is one of the only songs my mother ever learned to play on guitar). Despite its obvious tone of longing and sweet sorrow (or, “the comfort in being sad,” as Kurt Cobain once phrased it in Nirvana’s song from 1993 “Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge on Seattle”), and despite the fact that it contains nothing that even remotely concerns politics, the song was summarily banned in the 1970s by the military dictatorship that had seized power in Argentina. Perhaps with its root ethos of hope and perseverance they found the song as offensive and a threat to their agenda? That agenda being that which is always the ultimate aim of all tyranny: the complete subjugation and defilement of the soul.

To a family of Syrian-Lebanese origin, Cafrune was born August 8, 1937 on his parents’ ranch (La Matilde), which was located in the northern Argentine province of Jujuy. “El Turco,” as he came to be known, grew to be a gaucho cult figure, riding from town to town on horseback, always with a guitar and a song.

In 1977, at the age of forty and after spending several years living in Spain, Cafrune returned to Argentina, which was governed at the time by the brutal military dictatorship of Jorge Rafael Videla. During a performances at the Cosquín Folk Festival in January 1978, Cafrune refused to obey the interdict the regime placed upon one of his most-loved songs, stating: “Although it is not in the authorized repertoire, if my people requests it of me, I am going to sing it” (Ramos, 2004). Days later Cafrune was to begin a pilgrimage tour in honor of José de San Martín, who along with the likes of Simón Bolívar, and Uruguay’s own national hero, José Gervasio Artigas, helped liberate South America from the Spanish Empire in the early 1800’s.

Gral. José de San Martín—as depicted by amazing comic book artist ( The Cisco Kid, Hernán the Corsair) José Luis Salinas (Feb. 11, 1908—Jan 10, 1985).

My wife within Artigas’ Mausoleum: an underground room beneath his statue at the center of Montevideo’s Plaza Independencia

Intending to visit the capitals of each province, like a true gaucho this entire tour was to be conducted all on horseback.

As he set out upon his white horse on January 31, 1978, and under what could only lightly be described as “suspicious circumstances,” Cafrune was crushed by a passing truck in a “hit-and-run.” Nearly twelve hours later, on February 1, 1978, Cafrune succumbed to his severe injuries and died.

Cafrune in the 1970s

The rendition I present here is an amalgam, which features Cafune’s original recording of “Zamba De Mi Esperanza” synced up to one by the the Argentine quartet, Los Chalchaleros. Released in 2000 on their farewell double LP, Todos Somos Chalchaleros, Los Chalchaleros first gained international recognition with this song back in 1965. Formed in 1948 in the northern province of Salta, Los Chalchaleros are one of the most respected artists of traditional Argentinian folk music. With its sense of profound respect for both the material and for the man responsible for its ascendancy, I find this version particularly emotionally resonant.

“Zamba De Mi Esperanza”

Zamba, from my hope

You dawned like a longing.

Dream, dream from the soul

That sometimes dies without flowering.

Dream, dream from the soul

That sometimes dies without flowering

Zamba, I sing to you

Because your song spills love,

A caress of your kerchief

That wraps round my heart

A caress of your kerchief

That wraps round my heart

Star, you who looked

You who heard my pain,

Star, allow me to sing

Allow me to love as I do now.

Star, allow me to sing

Allow me to love as I do now.

Time, that goes by,

Like life, never returns.

Time is killing me

And your love will be, will be

Time is killing me

And your love will be, will be

Sunk on the horizon

I am dust taken by the wind.

Zamba, never leave me,

I, without your song, cannot go on living

Zamba, never leave me,

I, without your song, cannot go on living.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[21) Gioco di Bimba – Le Orme (1972)]

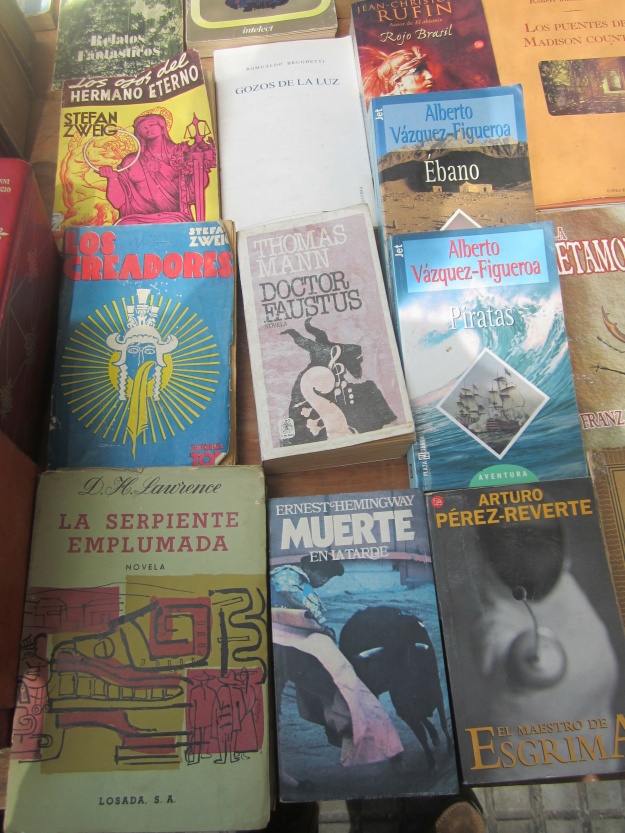

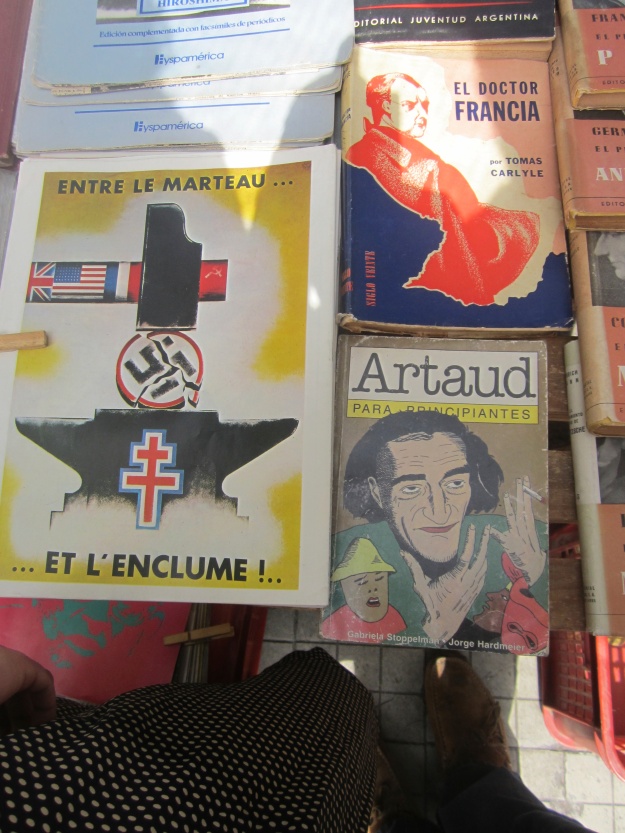

While making our way through the crowds gathered on a sunny Sunday morning for the vast flea market that encompasses numerous blocks surrounding the street of Tristán Narvaja in the middle of the Cordón neighborhood of Montevideo, I heard a song that immediately seized me. Side-stepping over to a tarp-covered table displaying a myriad of vinyl and CDs and stacked speakers bumping this haunting melody, I asked the gaunt and graying proprietor what was playing. After a suck and an exhale of his cigarette he excitedly handed me a CD case and asked in slight disbelief if I’ve never heard of the Italian prog-rock group Le Orme.

Staring at the cover art—an arresting oil painting by imaginative Italian artist Walter Mac Mazzieri (1947-1998) titled Garbo di Neve (which I believe translates to something like “The Grace of Snow”) and that features viscous colored gloops pulled and contorted into the cartoon shapes of sullen men, women, and beasts—I answered, “no.” Although now that I think of it I’m fairly certain that my uncle Raul attempted to get me into this group years and years ago when I was not quite prepared to tackle what prog-rock had to offer, this song sounded so strange and attractive. Within the sun-drenched textures of this ballad, behind the atmosphere of somnambulate ease created by a delicate interplay of acoustic guitar, the fanfare and waltz of synths, warm sing-along vocals, and the exquisite use of mandolin and clavinet that alternate between a caress and a tickle through the break—I sensed something deceitful, something wicked.

ImgFelSor400Concerto.jpg)

As it turns out this song—“Gioco di Bimba” (Game of The Little Girl)—is the second track off of Le Orme’s 1972 masterpiece, Uomo di Pezza (Rag Man). Having begun their career in Venice as another psychedelic pop group of the late 60s, by ’71 with their sophomore album Collage, Le Orme (The Footprints) had developed into a much more complex and symphonic set; this progression occurring despite now having been whittled down to a trio: Toni Pagliuca, keyboards; Aldo Tagliapietra, voice, bass, guitars; and Michi Dei Rossi, drums, percussion.

Operating almost as a concept album, at least in terms of its tone and themes if not as a fully fleshed out cinematic narrative, the seven tracks that make up their third LP Uomo di Pezza are threaded together by a poetic examination of spiritual and mental illness, violence, broken dreams, the depersonalization and anxiety of our modern world, and how men and women struggle to negotiate these while attempting to live in “reality.” Essentially, these songs concern the mystery and menace of the human condition, or as one erudite and perhaps mystic minded critic wrote on their Wikipedia page, “The lyrics of Uomo di pezza describe a helpless masculine attitude, juxtaposed to an unknown, inscrutable feminine universe.” Still my favorite track off of this brilliant work, “Gioco di Bimba” is a dream that sours into a nightmare of violation, repression, and the futility of repentance. By the end of this disturbing tale the Rag Man cannot stop repeating to his tailor (for what other God could there be for a Man of Rags?) “I did not want to wake her this way; I did not want to wake her this way,” but, horrifically, it matters little, for “in the game of the little girl, a woman loses.”

“Gioco di Bimba” (Game of The Little Girl)

As if by incantation she rises at night,

She walks in silence with eyes still closed

Like she’s following a magic song,

And on the swing returns to dreaming.

The long robe, the face of milk,

and moonbeams on thick hair.

The wax statue stretches out among the flowers,

The jealous goblins are spying.

Swinging, swinging, the wind pushes,

The stars are captured for his desires.

A furtive shadow is pried from the wall:

In the game of the little girl, a woman loses.

A cry in the morning in the middle of the road,

A man of rags calls to his tailor.

With a lost voice he forever repeats:

“I did not want to wake her this way,”

“I did not want to wake her this way.”

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[22) Siempre Caminar – Limonada (1970) [Snippet]]

Just an engaging snippet of the opening to Limonada’s “Siempre Caminar” (Always Walking). Limonada, being the project created by guitarist Walter Cambon and drummer Jose Luis Sosa after the dissolution of El Kinto, released only one album in 1970. Although overall a solid work with some true highlights and hooks, one certainly gets the feeling that something is missing, leaving you less than impressed. Or as Sosa himself expressed it:

With Limonada, Walter and I thought we wanted to continue

the lineage of El Kinto. I never liked Limonada. I do not like

anything about Limonada. Because something is missing. It is

something that is lame. Headless. The songs were there, musical

possibilities, the musicians even. What was missing? [Eduardo]

Mateo was missing. Or a mind like Mateo’s was missing, a genius

was missing. A dictator was missing, something of that

sort” (Peláez, 2004).

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

[23) Luna de Margarita – Simón Díaz (1966)]

Standing at the airport in the early a.m. and attempting to check in, my wife and I were informed at this last moment that we in fact were not permitted to board as our last connecting flight to New York had been cancelled due to impending snow storms that were anticipated to bury the eastern seaboard of The United States. Told that there were no other flights available to us for nearly a week, we were stranded in Montevideo. At least, that would have been the case if my beautiful family there did not immediately offer their home to us. They did so without even the slightest sigh of inconvenience.

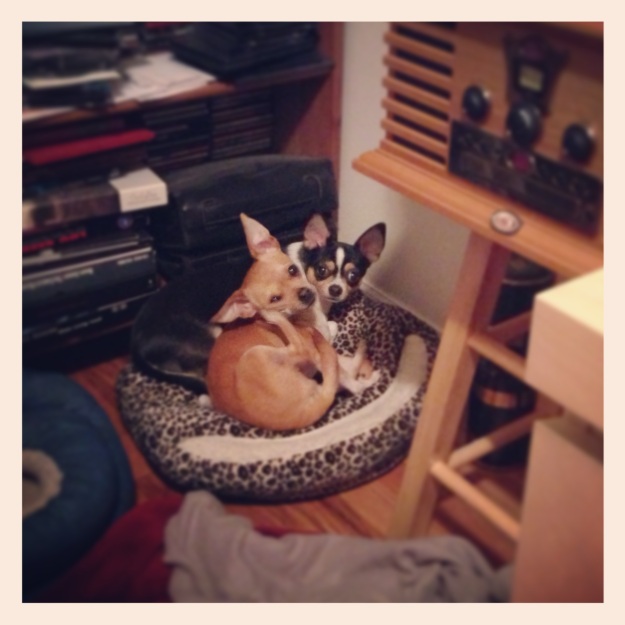

We spent these additional days walking Montevideo from top to bottom and I can say with confidence that we now know this city better than anyone in my immediate family back in NY, as they emigrated from their country only as they were entering their twenties. Also during this unexpected furlough (which often at times, albeit not unpleasant, felt much what limbo must be like) we were able to make a best new bud—my cousin’s dog: a scrappy little Yorkie named Luna. It was as if she could sense that the only thing we were truly homesick for from our lives back in Queens was our two little oddball Chihuahuas, Patti and Moose.

From our first afternoon at my aunt’s home on, Luna pursued and hoarded our affections, crawling into our bed to nap curled up between us and chasing off their other dog, a lumbering yet gentle German Shepard named Tango, whenever he attempted to enter our room. With a familiar light of demented acumen in her eyes, and a sweet, yet truly weird disposition akin to that of our own pups (I am convinced that Chihuahuas come with their heads already creatively wired when they’re born) she’d nudge our hands with her muzzle the moment we paused in our petting of her. She truly helped, and I’d often find myself singing this song to her in a mock mellifluous voice:

Luna de margarita es

Como tu luz

Como tu voz

Y como tu amor

Admittedly, my first contact with this tonada by Simón Díaz came from Devendra Banhart, with his much more spectral version released on 2005’s brilliant Cripple Crow.

Devendra Banhart with collaborators Andy Cabic, Noah Georgeson, and Thom Monahan. (Photo by Autumn de Wilde).