ADAM YAUCH, MCA: AUGUST 5, 1964 – MAY 4, 2012; R.I.P.

Unfortunately, it seems that lately the only time I feel compelled to take time out of my busy schedule to post on this blog is under the solemn circumstances of needing to pay my respects to an artist who has recently passed.

“Born and bred Brooklyn U.S.A./They call me Adam Yauch but I’m MCA”

MCA

Today, I pay such tribute to hip-hop pioneer and founding member of the Beastie Boys, Adam Yauch, aka MCA, aka Nathanial Hörnblowér. After a three-year battle with a cancerous parotid salivary gland, Yauch died on Friday, May 4th in his hometown of N.Y.C. He was 47. Yauch is one of the few celebrities whose death has actually had a strong emotional impact on me (the death of another NYC artist, Jim Carroll on September 11, 2009 is one from recent memory). Sure, when an artist whose work you enjoy dies you likely take note, but rarely does it truly upset you; rarely does it feel like a personal loss.

However, with each member of this triad being responsible for 33% of the aggregate sounds, images, attitudes, costumes, and overall vibe that is the life-long art project known as the “Beastie Boys” (I’ll leave that final 1% to be assigned to whatever collaborators, inspirations, and spiritual beliefs the group might wish to credit) the loss of Adam Yauch’s intrinsic creative input has effectively put an end to their singular voice, and it is a voice that will be sorely missed.

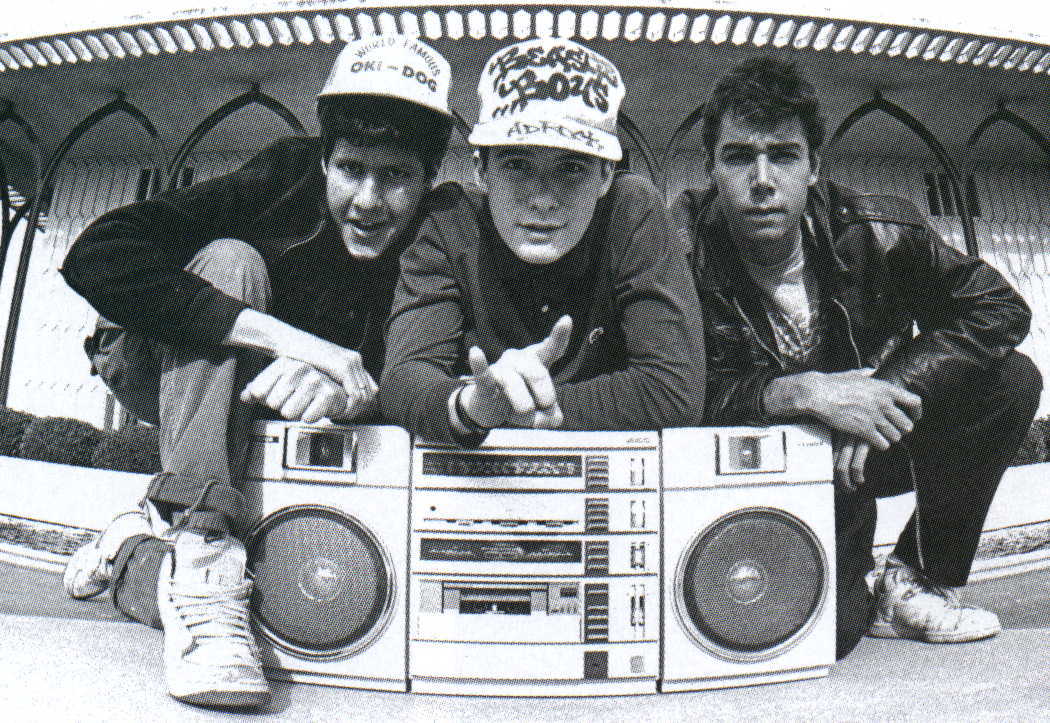

Along with Mike D and Ad-Rock, MCA’s Beastie Boys have created a most remarkable and enjoyable body of work through a career that has improbably endured over three decades. At their best, the Beastie Boys represent limitless possibility, and the promise of a good time to be had when exploring all these possibilities.

Regarding the death of their “brother,” an obviously grieving Ad-Rock sent out this image…

…while Mike D issued a statement that could also serve to characterize and sum up my feelings towards the Beastie Boys as a whole:

He really served as a great example for myself and so many of what

determination, faith, focus, and humility coupled with a sense of humor

can accomplish (Dillon, 2012).

As modern music, particularly within the genres of Rap and Hip Hop, has increasingly become pessimistic and irate (with dour faced men earnestly either adopting the supposed postures of thugs and hard-cases or acting emotionally fragile, alternately boasting and whining how they are all alone in this world and all the while clenching their teeth to convince you of their sincerity) the Beastie Boys and their overwhelming sense of camaraderie and levity have always been received as a welcome breath of fresh air. Furthermore, beyond these distinctive emotional qualities, sonically the Beastie Boys has been one of the most innovative recording artists to ever emerge. Over the years they have consistently explored and redefined the outer limits of popular sound and song construction.

Formed at the dawn of the 1980s in New York’s downtown art scene, the Beastie Boys began as a hardcore punk band, which served as a supporting act for notable groups such as the Dead Kennedys, Bad Brains, the Misfits, and Reagan Youth (Pollicino, 2009) at long-gone NYC venues like CBGB, A7, and Max’s Kansas City, and numerous other forgotten crawlspaces. Originally consisting of Manhattan-raised drummer/vocalist Michael “Mike D” Diamond, child of an interior designer and Harold Diamond, an eminent art dealer; Brooklyn-born bassist Adam “MCA” Yauch, the only child of Frances, a social worker and a public school administrator, and Noel Yauch, a painter and architect (LeRoy, 2006); the band also featured friend John Barry as the guitarist; and Kate Schellenbach, who would go on to play drums for the first act signed to the Beastie Boys’ own Grand Royal label: Luscious Jackson.

Adam “MCA” Yauch & Michael “Mike D” Diamond

In 1982, this line-up would release the EP Polywog Stew on the local independent label, Rat Cage. Perhaps the most memorable track on this release of noisy, rapid punks songs is “Egg Raid On Mojo,” as it memorialized one of the Beastie Boys then favorite pastime pranks of terrorizing friends as well as strangers by tossing raw eggs at them. This theme, as well as some of the lyrics would later be revisited in 1989 for the track “Eggman.”

———————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Like it? Buy it.

This album also featured the track “Holy Snappers,” for which the following accompanying video was made:

Soon afterwards, John Barry (Berry? I’ve read both) and Kate Schellenbach would leave the group only to be replaced by Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz. Horovitz—born in South Orange, New Jersey and raised in Manhattan by his mother Doris and his father, playwright Israel Horovitz—was the singer/guitarist for the punk rock band The Young and The Useless, which would often perform alongside the initial incarnation of the Beastie Boys (LeRoy, 2006). With the addition of Ad-Rock, the creative core of the Beastie Boys was now complete.

In 1983 the trio would release the EP Cooky Puss, the title track of which would be their first experimentation with hip hop: the song relying heavily on sampled vocals, turntable scratching, and processed beats, techniques most commonly associated with the still burgeoning style of music. The song’s title is a reference to Carvel’s delicious (I just bought one for my wife’s birthday last month) ice cream cake “Cookie Puss,” which is made in the shape of a face, with ice cream sandwiches serving as the eyes and an upside down sugar cone as the nose. As an interesting aside, Cookie Puss is intended to be a space alien born on the planet Birthday and his original name was “Celestial Person.” These initials were maintained, and later came to stand for “Cookie Puss.” Those who grew up in the NY area might recall the really whacked-out low-budget commercials produced by Carvel that featured Cookie Puss floating in space and speaking in a tweaked, pitch-shifted voice that’s kind of terrifying in retrospect.

The Beastie Boys’ song contains recordings of various crank calls the group made to a local Carvel restaurant, and it would become a local, underground hit single.

———————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Like it? Buy it.

After this minor hit, the Beastie Boys—who seem to have always had an uncanny ability to absorb their influences, only to subsequently reproduce, or extrapolate them rather, into something not only unique, but visionary as well—began to alter their sound, reorganizing into the now familiar formula of “Three MC’s and One DJ.” It was at this time that they were signed to Def Jam Recordings, a fledgling record label that had been run out of founder Rick Rubin’s NYU dorm room in Weinstein Hall on University Place right off Washington Square Park. Raised in Lido Beach, Rubin, that odd, bearded figure of old-school hip-hop had recently partnered with concert promoter/artist manager (and older brother of Rev. Run of Run-DMC) Russell Simmons. Simmons, raised in the Queens’ neighborhood of Hollis, had spent the past few years managing Kurtis Blow as well as his younger brother’s group (Tomassini , 2006) when he was introduced to Rick Rubin (I have read alternately that this introduction was done by Zulu Nation’s DJ Jazzy Jay, and by that multi-talented artist and all-around weirdo, Vincent Gallo).

Russel Simmons & Rick Rubin

At the time of the Beastie Boys’ signing, Def Jam was in the process of recording and releasing the debut single by a 17 year-old LL Cool J: “I Need a Beat,” which was co-written by Ad-Rock.

———————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Like it? Buy it.

This music and its scene were still in its infancy. It was an exciting time to be at its foundation and it was not only possible for a group of middle-class white boys to be signed based on their potential, but for them to actually become one the most popular and respected acts of the genre too.

Beastie Boys & Run-DMC

Def Jam soon released the Beastie Boys’ 1985 Def Jam debut single; the Rick Rubin produced “Rock Hard.”

———————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

The track prominently features a sample from the song “Back in Black” by AC/DC (a band I must admit I’ve always loathed). As these samples were used without obtaining legal permission, the record was soon withdrawn. In fact, when the Beastie Boys were compiling tracks for their 1999 career retrospective Beastie Boys Anthology: The Sounds of Science, Mike D reached out to AC/DC seeking permission for the inclusion of “Rock Hard” but was denied. As Mike D later stated: “AC/DC could not get with the sample concept. They were just like, ‘Nothing against you guys, but we just don’t endorse sampling.’” Ad-Rock then added, “So we told them that we don’t endorse people playing guitars” (NME, 1999). Ironically enough, around the same time as the Beastie Boys’ debut, the airline corporation British Airways created a commercial that illegally used a portion of “Beastie Revolution” off their Cooky Puss EP. The Beastie Boys successfully sued British Airways and used the money awarded them to rent a loft at 59 Chrystie Street in New York City’s Chinatown. This apartment was an ideal location for the group to rehearse loudly “into the wee hours, as it was conveniently located atop a sweatshop and a brothel” (LeRoy, 2006). This apartment was later memorialized as the title of the opening segment of their epic “B-Boy Bouillabaisse,” which closes the groups’ 1989 LP Paul’s Boutique, an album that would be simply impossible to create under today’s copyright and sampling laws as it uses an innumerable amount of samples.

Chinatown in the late ’70s

With its thick but bare-bones beats paired with heavy-metal guitar riffs, the steady measured delivery of which serve as a frame for the trio’s rapid, paroxysmal, and pinched approach to rhyming—the production formula for “Rock Hard” would serve as the basic template for the Beastie Boys’ 1986 debut LP, the Rick Rubin co-produced Licensed to Ill. It was an overwhelming success.

Licensed to Ill

They had spent the previous year building a fan base and a bad reputation with the release of “She’s on It” from the Krush Groove soundtrack, as well as supporting both John Lydon’s post-Sex Pistols project Public Image Ltd (PiL) and Madonna on her North American The Virgin Tour (apparently she and MCA were momentarily an item while on this tour). Now, with the release of their debut they were certified stars, as Licensed to Ill became one of the best-selling albums in history (Cameron, 2004).

Beastie Boys & Madonna: The Virgin Tour

A collection of juvenile fantasies—both rude and rudimentary—the album utilized samples from the likes of Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and even Creedence Clearwater Revival crammed with misogynistic lyrics and delirious wordplay that seemed to scream, “don’t take this too serious!” However, ridiculous as it may seem now, the Beastie Boys and their purported message was taken seriously by the watchdog facet of the media and they were deemed a serious threat to the decency of American youth. To my mind equally ridiculous, Licensed to Ill became the first rap album to reach #1 (BBC, 2012). It’s important to note, however, that despite its success there were many who viewed the group and its music as just plain stupid. Originally to be titled Don’t Be a Faggot, the album’s cartoon tales about drinking, drugging, robbing, rhyming, vandalism, gun-toting, and scamming on chicks were delivered in the unapologetic sneer of privileged delinquents, or as they themselves say on “The New Style”:

Some voices got treble, some voices got bass

We got the kind of voices that are in your face

Although being at the very least an amusing album (and still a lot of fun to shout along to), Licensed to Ill and its smash hit single “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party)” would leave one with the impression that the Beastie Boys were nothing but a one-trick-pony.

This single was further promoted (as the band’s image was further pigeonholed) with its now ubiquitous video, a quasi-riff on defiant party songs like Mötley Crüe’s cover of Brownsville Station’s “Smokin’ in the Boys Room” and the biker gang invasion scene of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead:

Looking back on this era of their lives and the reactions to the album (particularly how their sense of humor and ironic parodies seemed to be lost on a majority of their audience), the Beasties were quoted as saying:

MCA: We were definitely getting drunk and acting really stupid and

trying to purposely be obnoxious because we thought it was funny—

but we were also talking in the lyrics about smoking crack and smoking

dust and all the type of stuff that we weren’t actually doing. It was all

just stupid exaggeration.

Ad-Rock: And the press, at that time, would have believed anything.

So we just made shit up. It was kind of a goof. We’d just build on each

other’s stories. Like, yeah, we flooded the bathroom at the hotel, and

we sawed a hole in the ceiling so that we could go from one room to the

other.

Mike D: But once it gets printed one place that establishes it as fact.

I think the thing that we weren’t prepared for was when the exaggeration

stopped coming from us—when it went to the tabloid level. It took the

whole thing into a completely negative and kind of frightening and

alienating area. It’s easy to look back on it now, in this context, and see

it all leading up to that point. But at the time, we really didn’t know what

was happening (NME,1999).

As they embarked on their first headlining world tour (a beer-chugging, fist-pumping mess that featured dancing ladies in cages, a giant hydraulic penis, and crowds populated by frat-boys) the Beastie Boys were beginning to feel that the joke was perhaps wearing thin if not turning on them; they were starting to fear that they were actually becoming their own parody. Above all, the excess of the tour was simply wearing them out. The three were roughly only 21-years-old.

Licensed to Ill Tour, 1987

Licensed To Ill Tour, 1987

To further embitter them, producer Rick Rubin was receiving a majority of the creative credit for not only the music, but also the entire “Beastie Boy” persona. Years later, Russell Simmons admitted, “they didn’t have the credit they deserved early on for being creative” (LeRoy, 2006). Interestingly, one of the few tracks from the album that deviates from the rap/rock mold is the sample-spastic “Hold It, Now Hit It” (interpolating: “Drop the Bomb” and “Let’s Get Small” by Trouble Funk; “Funky Stuff” by Kool & The Gang; “Take Me to the Mardi Gras” by Bob James; “Christmas Rappin’” by Kurtis Blow; “La Di Da Di” by Doug E. Fresh and Slick Rick; and “The Return of Leroy” by The Jimmy Castor Bunch, who I’ve discussed earlier, here ) which was produced by the Beasties themselves and without Rubin’s input.

Coupling this lack of artistic recognition with the fact that they had yet to be paid by Def Jam (Simmons) an estimated $2 million in royalties, as they came off tour the three were just about ready to quit: whether they would depart from their label or quit being Beastie Boys altogether, I’m certain that they themselves were not sure of at the time. If they had left the project there and then, the Beastie Boys today would most likely be remembered as a novelty act, relegated to a footnote for the golden age of hip hop and only discussed during nostalgia driven programming for the purposes of demonstrating how ridiculous the tastes of the ’80s were.

What followed, however, is one of the most inconceivable tales of artistic reinvention, personal development, and the evolution of music…

—TO BE CONTINUED—

Stay tuned for I’VE BEEN COMING TO WHERE I AM FROM THE GET GO: Part II! Where we will explore the creation of Paul’s Boutique and the architects behind the Sounds of Science!

REST IN PEACE

————————-BOBBY CALERO————

Ref:

BBC. (2012, May 4.). Beastie Boys star Adam Yauch dies aged 47. BBC. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-17963855

Beastie Boys. (1982) Egg Raid On Mojo [recorded by Beastie Boys] On Polly Wog Stew [vinyl] Rat Cage. (1982). Re-released on Some Old Bullshit [CD] Capitol. (1994).

Beastie Boys. (1983) Cooky Puss [recorded by Beastie Boys] On Cooky Puss 12” [vinyl] Rat Cage. (1983). Re-released on Some Old Bullshit [CD] Capitol. (1994).

Beastie Boys. (1982) (Creators). Fiama22 (Poster) (2007, July 31). Beastie Boys – Holy Snappers punk [Video] Retrieved May 7, 2012 from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35YSM7zbV1w

Beastie Boys. (1986) (Creators). TheBeastieBoysVEVO (Poster) (2009, June 16). The Beastie Boys – Hold It Now, Hit It [Video] Retrieved May 7, 2012 from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oB0NM6reiRE&ob=av2e%20%5Bvid%5D

Beastie Boys. (1986) (Creators). TheBeastieBoysVEVO (Poster) (2009, June 16). (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party) [Video] Retrieved May 7, 2012 from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eBShN8qT4lk

Beastie Boys. (1985) Rock Hard [recorded by Beastie Boys] On Rock Hard 12” [vinyl] Def Jam Recordings. (1985).

Burns, M. E., (2000). The Beastie Boys. Pendergast, S., & Pendergast, T. (Ed.). St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, Vol. 1. 200-201. Detroit: St. James Press. Retrieved from Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Cameron, S. (2004). Beastie Boys. Wachsberger, K., & Laplante, T. (Ed.). Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Popular Musicians Since 1990, Vol. 1. 47-49. Detroit: Schirmer Reference. Retrieved from Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Carvel. (1985) (Creators). 0816brandon (Poster) (2012, April 16). Carvel’s Cookie Puss commercial [Video] Retrieved May 7, 2012 from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vjQpGeXnuio

Dillon, N. (2012, May 7.). Adam Yauch remembered: Beastie Boys’ Mike D and Ad-Rock open up on death of their ‘brother.’ New York Daily News. Retrieved from http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/music-arts/adam-yauch-remembered-beastie-boys-mike-ad-rock-open-death-brother-article-1.1074007#ixzz1uI94udC4

Horovitz, A., Smith, J., Rubin, R. (1984) I Need A Beat (Remix) [recorded by L.L. Cool J] On Radio [CD] Def Jam Recordings. (1985).

LeRoy, D. (2006). 33⅓ Paul’s Boutique. Continuum: New York.

New Musical Express. (1999, November 11). AC/DC nix Beastie Boys sample. New Musical Express. Retrieved from http://beastieboys.tumblr.com/post/291070903/ac-dc-nix-beastie-boys-sample

Pollicino, R. (2009). Gigography. Retrieved from BeastieMania.com..

Tomassini, C. (2006). Simmons, Russell. Palmer, C. A. (Ed.). Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, Vol. 5. 2035. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. Retrieved from Gale Virtual Reference Library.