underwater, it was

immediately strange

& familiar

from Paris Journal by Jim Morrison (1971).

In the early hours of July 3rd, 1969, founding member and celebrated multi-instrumentalist of The Rolling Stones, Brian Jones was found face down at the bottom of the swimming pool at his country house at Cotchford Farm. Located in East Sussex—about an hour’s drive from London—Cotchford Farm had once been owned by A.A. Milne who was inspired by the surrounding environs to create Winnie-the-Pooh, Christopher Robin, and their various friends’ adventures in the “Hundred Acre Wood” (and in this fact I’m sure lies the basis for a fun, psychedelic cartoon).

His body found by Janet Lawson, a 26-year-old nurse who was then dating The Rolling Stones’ tour manager Tom Keylock, and Jones’ girlfriend, Anna Wohlin, whether Brian Jones’ death was the result of murder committed by Frank Thorogood—a forty-three-year-old builder contracted to do work on the grounds but whose role had grown to a be a sort of “minder” for the unraveling Jones (Jones, 2008)—or was truly “death by misadventure” as the coroner’s official verdict stated will likely remain a rock ‘n’ roll mystery.

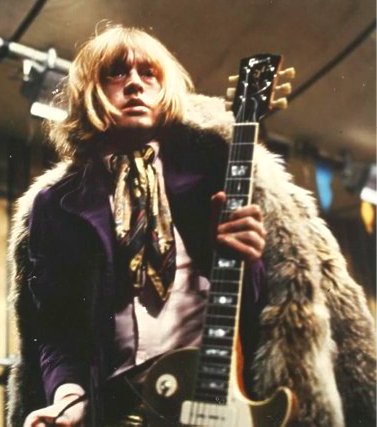

The last known photographs of Jones, taken by schoolgirl Helen Spittal on 23 June 1969, shortly after his departure from the Stones.

(Lewis) Brian (Hopkins) Jones was twenty-seven-years-old at the time of his death in 1969 and had only a month prior been asked to leave The Rolling Stones. On June 8, 1969, Jones was visited by Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, and Charlie Watts, and was told that the group that he had formed and named back in 1962 would now continue on without him. Permitted to announce the news as he saw fit, Jones issued a statement the next day announcing his departure, stating, “I no longer see eye-to-eye with the others over the discs we are cutting” (Wyman, 2002).

Brian Jones’ last picture with The Rolling Stones.

Jones’ being kicked out of the group has been seen with more than a critical eye over the years, with many choosing to see this as merely the result of greed and a power grab by “The Glimmer Twins” of Jagger and Richards. However, it needs to be recognized that not only did Jones’ numerous arrests and convictions for narcotics make it impossible for him to acquire a work visa to tour with the group, but that Jones’ excess and addictions had left him often unable—and more so averse—to contributing to the band’s music. It’s all well and good that Keith Richards was a junkie too, but at least he showed up and participated at rehearsals.

Brian Jones—in part because of his flamboyant sartorial style, beautiful boyish good looks, and the mass quantities of drugs and alcohol he would ingest—had been always held up as the figurehead for the group and had come to be celebrated as a Dorian Grey type figure. This, coupled with his skilled musicianship and true love of the blues, served to bridge the gap between London’s occultist dandies and the dirty music of the American south (Hill, 2011). There are many who believe that The Stones’ claim to greatness ended with Jones’ departure, but I (as anyone who’s listened to their double LP of 1972, Exile on Main St.) strongly disagree. However, Brian Jones’ influence and contribution to this group cannot be expressed enough.

Never a songwriter but rather a true musician, Jones had an uncanny ability to pick up any instrument and add that essential and odd element that would distinguish The Stones from every other R&B bar band of the swinging scene of London in the ’60s: think of the sitar on “Paint It Black,” the marimbas on “Under My Thumb,” or the dulcimer on “I Am Waiting.”

Jones’ talent did not only lie in implementing instruments hitherto unknown in the musical lexicon of rock ‘n’ roll, but extended to the flavor he could add with more traditional instruments such as harmonica, guitar, and keyboards. Brian Jones was simply ingenious at creating the proper moods and appropriate atmospheres a song required. He was style, and he was content. For example, consider his bottle-neck guitar on 1968’s Beggars Banquet track, “No Expectations.” Other than Jagger’s pouty-mouthed vocals of lament, it is Jones’ contribution that imbues the song with its thick syrup of loneliness.

The original cover photo for Beggars Banquet (photo by Michael Joseph).

———————————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Like it? Buy it.

However, by the time of this song’s recording in the summer of 1968 Jones’ enthusiasm for the group had waned and his contributions became less and less. Mick Jagger later stated in a 1995 interview for Rolling Stone “We were sitting around in a circle on the floor, singing and playing, recording with open mikes. That was the last time I remember Brian really being totally involved in something that was really worth doing” (Wenner). In fact, upon being dismissed from the group Jones nearly immediately contacted Mitch Mitchell (drummer for The Jimi Hendrix Experience) about the possibility of beginning a new band together. Jones had recorded with him before (along with Hendrix himself, as well as Traffic guitarist Dave Mason) in a session at Olympic Studios in London with Chas Chandler producing and Eddie Kramer engineering. Held on December 28th 1967, this session was conducted during the initial recording dates for Jimi Hendrix’s masterpiece, Electric Ladyland, before Hendrix moved production to the newly opened Record Plant Studios in New York the following spring.

The alternate cover for 1968’s Electric Ladyland (photo by David Montgomery)

Jones had grown to be quite friendly with Hendrix and his group and had in fact introduced them on stage to the audience at The Monterey Pop Festival held in June of 1967 (effectively introducing Hendrix to America itself, as he had little recognition in the states up until this point—Hendrix cemented his prominence by famously ending his performance by setting his psychedelically painted Fender Stratocaster on fire in what seemed liked some sensual, voodoo ritual).

Brian Jones introduces The Jimi Hendrix Experience to America in 1967 at The Monterey International Pop Music Festival

Despite often being characterized as “over-sensitive” (a disposition that frequently lends itself to acts of manipulation and cruelty) of all the Stones only Brian was adored by the community of musicians, artists, and general audience springing from the counterculture of the ’60s; of all the Stones only Brian was invited to record with their rivals, The Beatles: in mid-May of 1967 playing oboe on “Baby, You’re a Rich Man” and alto sax on “You Know My Name (Look Up the Number).”

London, 1968: Brian Jones, Donovan, Ringo Starr, John Lennon, Cilla Black, and Paul McCartney.

Yoko Ono, Brian Jones, Julian and John Lennon,1968.

The Jones/Hendrix session would produce only two alternate takes of a single instrumental composition entitled “Little One,” which despite its impressive structure and performance remains unreleased to this day. As the two takes are incredibly similar, with one noticeable difference being Hendrix implementing a slide to his guitar on “take 2,” I have never been able to decide which I enjoy more…and so I present them both to you.

“Little One (take 1)”

——————————————(CLICK TO LISTEN)

“Little One (take 2)”

———————————————(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Brian Jones – Sitar and percussions

Jimi Hendrix – Guitar

Dave Mason – Bass and sitar

Mitch Mitchell – Drums

Brian Jones & Anita Pallenberg

Jones’ penchant for excess had been exacerbated by his intense romantic affair with Italian-born actress, model, sexpot bombshell, and epicurean, Anita Pallenberg. She has been described as powerful, brilliant, and absolutely mad; all often in the same breath.

Anita Pallenberg as The Black Queen/The Great Tyrant in Roger Vadim’s cult-classic sci-fi film of 1968, Barbarella.

Anita with co-star Jane Fonda in the titular role of Barbarella.

Jones and Anita together were known to over-indulge in narcotics and sex, and often their relationship would delve into dark, sadomasochism.

However, in 1967 while Keith Richards, Jones, and Pallenberg were vacationing together in Morocco, Richards and Pallenberg began an affair after Jones became ill and was checked into a hospital. Eventually Pallenberg left Jones for Richards and the two had a relationship that lasted until 1980 and which resulted in numerous children (as well as accelerated drug abuse). Perhaps as much as boredom and dependency, this betrayal led to Jones’ dissolution from The Rolling Stones. For, as much as “the hippies” advocated a free-love philosophy, it remains a philosophy that is much more difficult to put into practice than it is to place as a slogan on a placard.

Brian Jones, Anita Pallenberg, and Keith Richards in 1967.

Jones’ continuing substance abuse led to a fragile state of mental health, marked by paranoia, distraction, and even violent outbursts. Yet, despite all this, as I have said, Jones remained the adored golden-haired child of the ’60’s. Upon Jones’ death numerous songs were performed in his name, Pete Townshend wrote a poem titled A Normal Day for Brian, A Man Who Died Every Day, and in Hyde Park on 5 July 1969, The Rolling Stones performed a free concert in Jones’ honor (as well as to introduce new member and brilliant guitarist, Mick Taylor). Stagehands released hundreds of white butterflies as part of the tribute (many had already suffocated in their crates and so were tossed dead onto the audience) and Jagger read excerpts from Adonais, a poem by Percy Shelley concerning the death of his friend John Keats:

I weep for Adonais -he is dead!

O, weep for Adonais! though our tears

Thaw not the frost which binds so dear a head!

And thou, sad Hour, selected from all years

To mourn our loss, rouse thy obscure compeers,

And teach them thine own sorrow, say: “With me

Died Adonais; till the Future dares

Forget the Past, his fate and fame shall be

An echo and a light unto eternity!

The Rolling Stones in Hyde Park on 5 July 1969.

Marianne Faithfull

However, it should be noted that Watts and Wyman were the only members of The Rolling Stones who actually attended Jones’ funeral. Neither did Pallenberg attend. Concerning this absence and its effects, Marianne Faithfull has written:

Brian’s death acted like a slow-motion bomb, It had a

devastating effect on all of us. The dead go away, but

the survivors are damned. Anita went through hell from

survivor’s guilt and guilt plain and simple. She developed

grisly compulsions…Keith’s way of reacting to Brian’s

death was to become Brian. He became the very image of

the falling down, stoned junkie hovering perpetually on the

edge of death. But Keith, being Keith, was made of different

stuff. However he mimicked Brian’s self-destruction, he

never actually disintegrated (Greenfield, 2006).

It is rumored that it was Bob Dylan who paid for Brian Jones’ extravagant casket. Perhaps it was intended as a form of apology? For as Daniel Mark Epstein writes in his highly engaging biography/memoir, “The Ballad of Bob Dylan,” from a passage concerning Dylan’s inclination towards cruel, acerbic words spat at those he viewed as pestering him while he and confidant Bobby Neuwirth held an amphetamine-fueled court (performing “mental gymnastics”) at New York clubs like Max’s Kansas City:

Brian Jones, the gifted, exquisitely sensitive English guitarist

who founded the Rolling Stones, idolized Bob Dylan. Jones was tiny,

an inch shorter than his hero, blond-haired, blue-eyed, and

androgynous looking, sporting frilly Edwardian blouses and bright

scarves. He was notoriously volatile, needy, and drug dependent.

By and by Neuwirth led him toward the table where the maestro

was holding court.

Neuwirth welcomed the celebrated multi-instrumentalist who

had taught Mick Jagger how to play harmonica. Dylan bared his teeth.

First of all he declared the Stones were a joke—they could not be taken

seriously. Now everyone could laugh at that, true or not, because the

comment cost nothing, drew no blood. But then he explained to Jones

that he had no talent and that the band, joke that it was, ought to replace

him with someone who could sing. This made Jones unhappy, after all

he had been so happy to see Dylan in the bar. The Englishman swept his

flowing hair out of his eyes, which were tearing up as Dylan went into

detail about Jones’ musical handicaps. Jones began to cry. Now the whole

mob could see his weakness; it was a terrible sight, the flowing locks, the

lacy sleeves, the weeping—just the wrong image for a group called

“The Rolling Stones.” Dylan concluded. He may have been right; Jones

did not seem to be long for the Rolling Stones, or this world, for that matter.

A couple of years later he was found dead at the bottom of a swimming pool.

Some say that Dylan paid for Jones’ lavish coffin (2011).

Brian Jones and Bob Dylan attend a release party for the Young Rascals at the Phone Booth nightclub in New York City in November, 1965. (photo by Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)]

Nearly immediately after Jones’ death (possibly even the day it was reported) lead singer for The Doors, Jim Morrison composed the poem: Ode to L.A. While Thinking of Brian Jones, Deceased:

I’m a resident of a city

They’ve just picked me to play

The Prince of Denmark

Poor Ophelia

All those ghosts he never saw

Floating to doom

On an iron candle

Come back, brave warrior

Do the dive

On another channel

Hot buttered pool

Where’s Marrakech

Under the falls

the wild storm

where savages fell out

in late afternoon

monsters of rhythm

You’ve left your

Nothing

to complete w/

Silence

I hope you went out Smiling

Like a child

Into the cool remnant

of a dream

The angel man

w/ Serpents competing

for his palms

& fingers

Finally claimed

This benevolent

Soul

Ophelia

Leaves, sodden

in silk

Chlorine

dream

mad stifled

Witness

The diving board, the plunge

The pool

You were the bleached

Sun

for TV afternoon

horned-toads

maverick of a yellow spot

Look now to where it’s got

You

in meat heaven

w/ the cannibals

& Jews

The gardener

Found

The body, rampant, Floating

Lucky Stiff

What is this green pale stuff

You’re made of

Poke holes in the goddess

Skin

Will he Stink

Carried heavenward

Thru the halls of music

No chance.

Requiem for a heavy

That smile

That porky satyr’s

leer

has leaped upward

into the loam

———————————————————

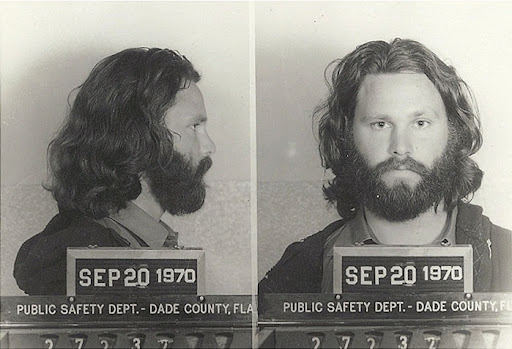

Jim Morrison in the Summer of 1969.

- One Jim Morrison’s final notebook from his time in Paris, 1971.

Despite its obvious merits to any literate that would take the time to read it, the poetry of Jim Morrison has always been too casually dismissed. This dismissal mostly comes as a flippant reaction to the audience who have come to embrace Jim Morrison: generally comprised of awkward adolescents and teenagers who believe they are obsessed with death—when in actuality it is sex and a sense of discovery that has strangled their brains. Often, for this group of admirers it’s not even the man Morrison they cling to but the dark image of him, the risk and pleasure he represents. Yet, developing and hormone-addled youth shouldn’t be judged here, nor their easy acceptance of projected iconography that has certainly been marketed towards them; but the adult academics and intellectuals who continue to not only disregard the man’s work, but actually let out a little chuckle of disdain at his mention do deserve a harsh word or two.

To my mind and tastes Jim Morrison was a truly gifted American poet with a distinctive American voice and cadence that should be appreciated and celebrated, as Whitman’s is, as Robert Frost’s is, as Hart Crane’s is.

Again, he is dismissed because he was a rock star, but who could argue that if Rimbaud had come of age during the 1950s and 1960s in the United States that he wouldn’t have pursued the decadence of rock ‘n’ roll as a form of artistic expression before abandoning it all for the world of commerce?

Another factor for the lack of recognition (if not contempt) for Morrison’s writing is the confounding of his lyrics with his poetry. Although the two are not always mutually exclusive, for the most part they remain two different animals. Whereas Morrison might have crooned into your ear that there were “weird scenes inside the goldmine,” within his poems he could go on to meditate on these scenes, and although odd, it’s also all so very familiar:

I have a vision of America

Seen from the air

28,000 ft. and going fast

A one armed man in a Texas

parking labyrinth

A burnt tree like a giant primeval bird

in an empty lot in Fresno

Miles and miles of hotel corridors

& elevators, filled with citizens

(circa 1969)

There are certain conventions and limitations placed upon a lyricist that might work splendidly while sung along with the buzz and hum of an electric guitar or the roll of a drum but that nevertheless fall flat or seem simply self-indulgent when read upon the page. With the verse, notes, and fragments of dialogue that he constantly scrawled into the notebooks he always carried, Morrison could drop any “Lizard King” posturing of his rock ‘n’ roll persona and indulge in what he always saw as his true work: poetry.

Freeways are a drama, a new

art form. Signs. Houses.

Faces. Loud gabble of Blacks

at a bus stop.

With lines like these from the ending stanza of his poem The Guided Tour, or others such as “The bus gives you a hard-on/with books in your lap” Morrison was attempting honest artistic communication of a facet of the American experience, and more so the human condition. There are certainly lines of both Morrison’s lyrics and his poetry that come off as silly, but it should be remembered that he was still only a young man in his twenties and searching for his “voice.” This search itself is actually one of the aspects of his work that I find makes it so enjoyable. Additionally, despite the calculated images of a serious young Adonis with a svelte naked torso writhing in tight leather pants across many a teenager’s t-shirt, it should be noted that Morrison could be an incredibly goofy guy. For a more humanistic view of the man than the mystic hedonist that is traditionally depicted, I highly recommend you watch Tom DiCillo’s 2009 documentary When You’re Strange, narrated by Johnny Depp.

The dichotomy presented by the easy access to excess and fun afforded by being a rockstar butting up against a desire to pursue his literary ambitions with a serious, sensitive intelligence had begun to wear on Morrison fairly early into The Doors career. This discord—coupled with his highly addictive personality—led Morrison to begin drinking heavily, wander off, and participate less in the band’s creative/recording sessions; particularly for their third and fourth LPs, 1968’s Waiting for the Sun, and The Soft Parade, released in 1969.

Morrison in the closet of his room at LA’s Chateau Marmont hotel, May 1968, as The Doors were finishing recording sessions for Waiting For The Sun. (photo by Art Kane).

By 1969 Morrison often seemed dissatisfied if not outright bored with The Doors and their music, but had been dissuaded from quitting by the other members. He would go on to state in an interview with CBC Radio, “I’m hung up on the art game, you know? My great joy is to give form to reality. Music is a great release, a great enjoyment to me. Eventually I’d like to write something of great importance. That’s my ambition—to write something worthwhile” (Nester, 2011). His growing lack of interest in the music is occasionally evident in the band’s creative output of the time. This statement is in no way meant to disparage the music of The Doors, as I still believe to this day that together, keyboardist Ray Manzarek, drummer John Densmore, and guitarist Robby Krieger had one of the most singular sounds ever created by a rock band. I’m not even certain they qualify to be labeled as “rock.”

Cinematic in scope and theatrical in presentation, The Doors fluidly merged jazz associated time signatures with Latin rhythms, the primitive stomp and lustful swagger of the blues, and the sinister yet jaunty gait of a vaudevillian circus—the whole sound given flight by extended flourishes of flamenco, surf-rock riffs, and sharp apoplectic convulsions of psychedelia. Inexplicably, this sound could still urge the listener to tap his foot and sing along. Play any album by The Doors and tell me what other group (even those that are attempting to emulate) sounds like this? I suppose the only appropriate genre label for this group would be “weird.” Yes, they were a band of weirdos.

Take for example their performance of “Universal Mind” on the night of July 21st, 1969, where a showtune lament suddenly cascades to take on Mongo Santamaría’s “Afro Blue” (in an arrangement made famous by John Coltrane in 1963):

“Universal Mind” July 21st, 1969

—————————————–(CLICK TO LISTEN)

When at their best, what distinguishes this group’s sound from the majority of their contemporaries is that they not only sound extraordinarily alive and on a journey, but filled with dread at the awesome wonder of being so; the sound of there being “something not quite right.” It is that underlying but persistent sense of creation confronting dread that has bestowed their music with longevity despite (or perhaps as a side-effect of?) our desperate-for-the-next-hit culture. However, by the time The Doors were completing The Soft Parade, it seems Jim Morrison had grown fed up with the band and what the audiences expected of them, frustrated with his literary ambitions, and more so disgusted with both himself and the state of American affairs.

Being drunk is a good disguise.

I drink so I

can talk to assholes.

This includes me.

(from As I Look Back).

Could any hell be more

horrible than now

and real?

(from Lament For The Death Of My Cock, 1969)

Do you know we are being led to

slaughters by placid admirals

& that fat slow generals are getting

obscene on young blood

Do you know we are ruled by T.V.

(from An American Prayer, circa 1970)

On March 1st, 1969 The Doors were scheduled to kick-off of their biggest tour ever by playing the Dinner Key Auditorium in the Coconut Grove neighborhood of Miami. Morrison had spent the week prior regularly attending performances by The Living Theater in California. These performances were meant to challenge conventional notions on love, decency, morality, and freedom of expression, and featured scantily dressed and nude actors both on stage and interacting directly with the audience. Inspired, Morrison has all this in mind when he steps on stage. However, after fighting with his girlfriend Pamela Courson, he has also spent the entire day drinking and missing connecting flights to Miami. Arriving late, he is extremely intoxicated.

A converted seaplane hanger, the Dinner Key Auditorium is filled well beyond capacity (the promoters had taken out the chairs in order to sell more tickets) and the air is stifling from the Florida heat. The performance that evening will be considered a disaster and would end abruptly when the stage collapses under the weight of the audience that had rushed up there at Morrison’s insistence. Morrison himself would be tossed into the crowd by an overwhelmed security guard. Afterwards, the Dade County Sheriff’s office issued a warrant for Morrison’s arrest claiming that he had deliberately exposed his penis while on stage, shouted obscenities to the crowd, simulated oral sex on guitarist Robby Krieger and was drunk at the time of his performance, he would be accused as well by the press of attempting to incite a riot. Although the man certainly was inebriated and did use “obscene” language, and the concert itself was perhaps not the best example of professional musicians, what occurred was a man’s impassioned plea for a spirit of brotherly love to permeate our cold, war-profiteering culture, and for the people to “wake up” from their lulled stupor, submissive to every sadistic and avaricious whim of a ruling elite; an elite that today is popularly called the “one percent.”

“You’re all a bunch of fuckin’ idiots! Lettin’ people tell you

what you’re gonna do! Lettin’ people push you around! How long do

you think it’s gonna last? How long are you gonna let it go on? How

long are you gonna let em push you around? How long? Maybe you

like it. Maybe you like being pushed around! Maybe you love it! Maybe

you love getting’ your face stuck in the shit! Come on! You love it,

don’t ya! You love it! You’re all a bunch of slaves. Letting everybody

push you around. What are you gonna do about it! What are you gonna

do about it!”

With these fervent words, and his repeated assertions of, “I aint talkin’ about no revolution, and I’m not talking about no demonstration, I’m talkin’ about having a good time; I’m talkin’ ‘bout love,” as well as his commands that the audience “love your neighbor ‘till it hurts,” Morrison might have been drunk but his message was still as poignant and passionate as those by any other concerned citizen, such as those by my favorite comedian (and philosopher) Bill Hicks, who twenty-four years later told his American audiences:

“The world is like a ride in an amusement park, and when you choose to go on it you think it’s real because that’s how powerful our minds are. The ride goes up and down, around and around, it has thrills and chills, and it’s very brightly colored, and it’s very loud, and it’s fun for a while. Many people have been on the ride a long time, and they begin to wonder, ‘Hey, is this real, or is this just a ride?’ And other people have remembered, and they come back to us and say, ‘Hey, don’t worry; don’t be afraid, ever, because this is just a ride.’ And we … kill those people. ‘Shut him up! I’ve got a lot invested in this ride, shut him up! Look at my furrows of worry, look at my big bank account, and my family. This has to be real.’ It’s just a ride. But we always kill the good guys who try and tell us that, you ever notice that? And let the demons run amok … But it doesn’t matter, because it’s just a ride. And we can change it any time we want. It’s only a choice. No effort, no work, no job, no savings of money. Just a simple choice, right now, between fear and love.

“The eyes of fear want you to put bigger locks on your doors, buy guns, close yourself off. The eyes of love instead see all of us as one. Here’s what we can do to change the world, right now, to a better ride. Take all that money we spend on weapons and defenses each year and instead spend it feeding and clothing and educating the poor of the world, which it would pay for many times over, not one human being excluded, and we could explore space, together, both inner and outer, forever, in peace.”

For the most part, Morrison’s rants that evening made it impossible for the band to play through any of their hits as he insisted on repeatedly directly communicating with the audience, and his inebriated state seemed to rattle their typically intuitive musical communication. Essentially, it was not a great show. However, there are moments that are great examples of raw, blistering, “rock-out-with-your-cock-out” (pun intended) music. Morrison’s voice itself here exemplifies what he once wrote in one of his notebooks under the title of As I Look Back:

Elvis had sex-wise

Mature voice at 19

Mine still retains the

nasal whine of a

repressed adolescent

minor squeaks & furies

An interesting singer

at best—a scream

or a sick croon. Nothing

in-between.

The following track has been slightly edited by myself to focus upon the more poignant and entertaining moments, in terms of this discussion:

The Doors, March 1st, 1969

——————————————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

The Doors live at the Dinner Key Auditorium, Miami (March 1st, 1969):

Are you Ready/Back Door Man/I Want Some Love/Five To One/Talkin’ Bout Some Love/Touch Me/I Was Born Here/Light My Fire/I Wanna See Some Action.

After the “Miami Incident” The Doors had found that the majority of their tour had been cancelled by the venues, as they were no longer willing to host them. Later that month Jim Morrison uses the forced lull in touring as an opportunity to record some of his poetry without the presence of the other members of The Doors. One of the finest of these recordings features Morrison’s memories of attending high-school dances as an army brat (his father was Rear Admiral George Stephen Morrison and happened to be in command of the Carrier Division during the controversial Gulf of Tonkin Incident in 1964—how’s that for a generation gap?). This piece is titled, Can We Resolve The Past?:

Jim Morrison in 1964 (photo by Alain Ronay).

——————————————(CLICK TO LISTEN)

On Monday, April 28th, after further cancellations and the possibility of a three-year sentence in a Florida prison hanging over Morrison’s head, The Doors entered PBS Studios in New York to record for the show “PBS Critique.” Along with several other songs they performed their blues vamp “Build Me A Woman,” as well as the psychedelic epic (and title track) that closes The Soft Parade, which was due to be released on July 18th. A rarity for them performance wise, “The Soft Parade” is another fine example of my earlier statements regarding the total idiosyncratic nature of The Doors’ sound.

With their entire American tour cancelled, the group accepted an offer to perform at The Forum in Mexico City for four dates at the end of June.

The Doors in Mexico, June 1969

It would have been returning from this brief engagement in Mexico that Morrison would have first learned of Brian Jones’ death and subsequently compose his poem, Ode to L.A. While Thinking of Brian Jones, Deceased. Shortly after, with The Doors securing the two nights of July 21 and 22 at the Aquarius Theatre on Sunset Blvd, Hollywood, Morrison would self-publish this work and distribute it freely to those in attendance. To his irritation, the majority of The Doors’ audience, who only seemed to come to shows in anticipation of a spectacle, left these chapbooks to litter the floor—unread.

The Doors at the Aquarius Theatre.

On the evening of the 22nd, Morrison would tell the audience: “Hey, I’m tired of being a freaky musician; I want to be Napoleon! Let’s have some more wars around here. What a stinking, shitty little war we have runnin’ over there. Let’s get a big one! A real big one! With alotta…killings, and bombs, and blood!” A little over two weeks later, a man and three women, “hippies” by all accounts and members of a cult, would enter a luxurious home in the Benedict Canyon area of Los Angeles and butcher five people, including actress Sharon Tate who was eight-months-pregnant at the time. They were directed by one man: Charles Manson. The “Manson Family” would later be arrested in Death Valley where they had been living while searching for a hole in the earth that would lead them to a fabled underground city. Four months after this concert the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam (in which roughly 500 unarmed Vietnamese men, women, the elderly, as well as children and babies were murdered by the U.S. military) becomes public knowledge after being suppressed for some twenty months by the government.

At this show The Doors also debut some preliminary compositions for the album they would record at the end of the year, Morrison Hotel, subsequently released in February of 1970. Of this material, one highlight is the live rendition of “Maggie M’Gill”

——————————————————–(CLICK TO LISTEN)

![December 1969, Los Angeles, CA – Jim Morrison stands amidst a group of men outside the original Hard Rock Cafe in the skid row area of downtown L.A. – Image by © Henry Diltz/Corbis]](https://theselvedgeyard.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/dz0023971.jpg?w=640&h=432)

December 1969, Los Angeles, CA – Jim Morrison stands amidst a group of men outside the original Hard Rock Cafe in the skid row area of downtown L.A. – Image by © Henry Diltz/Corbis]

December 1969, Los Angeles, California, USA — The Doors dine in a Mexican restaurant. From right to left: Jim Morrison, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, and Robbie Krieger. — Henry Diltz

At the time of recording Morrison Hotel, it seems that Morrison’s lyrics and poetry begin to achieve a certain new level of maturity, as well as gaining a synthesis of vision between the two. As a poet, as a lyricist, as an “old bluesman,” Morrison comprehended the pure expression—the psychic communication—that can be achieved through symbolism. I believe the music itself on this album (and the next and last, L.A. Woman) reflects this. Many claim that these albums were “a return-to-form” but in reality The Doors had never sounded quite like this. Although by no means did Morrison cease his self-abuse, it does seem that he and his long-time girlfriend (wife, for all intents and purposes) did reach a level of stability, and that Morrison, at her urging, dedicated himself towards his writing more fully.

![(photo by Raeanne Rubenstein)]](https://amouthfulofpennies.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/jim2bmorrison2bcdcdf528e9.jpg?w=500&h=495)

(photo by Raeanne Rubenstein)

Jim & Pam (edmund teske 1969)

While touring to promote this album, on April 7th Morrison had two poetic works bound together and published in one volume: The Lords and The New Creatures. The first half—The Lords—with its subtitle “Notes on Vision,” contains numerous thoughtful essay-like meditations on the human-condition in relation to his ability to experience reality, particularly in light of modern advancements in his ability to create the pictorial through the cinema. This work also explores both the liberation to be found in being an artist as well as the sinister element of subjugation that can occur through all this.

“There are no longer ‘dancers,’ the possessed.

The cleavage of men into actor and spectators

is the central fact of our time. We are obsessed

with heroes who live for us and whom we punish.

If all the radios and televisions were deprived

of their sources of power, all books and paintings

burned tomorrow, all shows and cinemas closed,

all the arts of vicarious existence…

“We are content in the ‘given’ in sensation’s

quest. We have been metamorphosised from a mad

body dancing on hillsides to a pair of eyes

staring in the dark (p. 29)

“More or less, we’re all afflicted with the psychology

of the voyeur. Not in a strictly clinical or

criminal sense, but in our whole physical and

emotional

stance before the world. Whenever we seek to break

this spell of passivity, our actions are cruel and

awkward and generally obscene, like an invalid who

has forgotten to walk (p. 39).

“The Lords appease us with images. They give us

books, concerts, galleries, shows, cinemas.

Especially the cinemas. Through art they confuse

us and blind us to our enslavement. Art adorns

our prison walls, keeps us silent and diverted

and indifferent” (p. 89).

Beginning the “Roadhouse Blues Tour” on January 17th 1970 at the more intimate Felt Forum within Madison Square Garden in New York, those born after a certain era have always been given the impression through marketing that The Doors had past their prime once Morrison had put on pounds, grown a beard, and abandoned the leather pants for jeans and a t-shirt. However, I believe the band has never sounded as dynamic and fully engaged with the music as they did on this tour. In fact the majority of live recordings you’ve most likely heard from this group, despite the “young lion” images of Morrison emblazoned on the LP covers, come from this era. It seems that at the band’s beginnings Morrison had calculated a figure so powerful and alluring that there was nothing he could do to destroy it.

As a demonstration of the band’s prowess at this time, check out what perhaps might be their finest live performance ever put on tape: from Saturday, May 2nd at The Pittsburgh Civic Arena, here’s “Roadhouse Blues.”

——————————————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Like it? Buy it.

Concerning the song and this performance, cultural historian and critic Greil Marcus (who, to those familiar with my blog by now must realize is one of my favorite go-to-guys for critical insight) had this to say:

“In Pittsburgh, on May 2, 1970, for the fourth number of the set, the band hammers into the song. It will take them seven minutes to tease, demand, threaten the song to force it to give up every secret it was made to reveal, and the drama unfolds when Morrison, his voice already desperate, preternaturally full, expanding with each line, descends into the bubbling swamp of the tune, the place without words. He disappears into the maw of the music and keeps going, you gotta cronk cronk cronk sh bomp bomp cronk cronk eh hey cron cronk cronk ado ah hey che doo bop dag a chee be cronk cronk well rah hey hey tay cronk cronk see lay, hey—he sustains it all for a solid minute. It’s harder than it looks. With each measure of vocal sounds the pressure is increased, the pleasure is deeper, the abandon more complete, the freedom from words, meaning, song, band, hits, audience, police, prison, and self more real, precious, and sure to disappear around the next turn if you don’t keep your eyes on the road. In that long minute, Morrison sings the whole song in another language, one only he could speak, but that anyone could understand. There is no document he left behind where he sounds more fulfilled as an artist, as someone who threw down the gauntlet and said to himself, to you, to whoever was listening, to whoever wasn’t, follow that” (2011).

Another fine example is their performance of “Love Me Two Times,” from August 21st at the Bakersfield Civic Auditorium in California. Here they effortlessly let the song drift where Morrison takes it, incorporating elements of the blues standard “Baby Please Don’t Go” (first recorded by Big Joe Williams in 1935), and “St. James Infirmary Blues,” that anonymous American ode to love lost through iniquity, made famous by Louis Armstrong in 1928 and covered countless times since.

(photo by Michael Parrish)

—————(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Having turned down an offer to perform at the Woodstock Festival, The Doors now agreed to play what was intended as the European version, located at the East Afton Farm on an area on the western side of the Isle of Wight.

Morrison would spend the following two months on trial for obscenity, but what was truly on trial was not only an artists’ right to express himself, but any American citizens’ right to do so. After a state-sponsored “Rally for Decency,” the Miami jury (the youngest member was 42 years old) convicted Morrison on misdemeanor counts of indecent exposure and open profanity while acquitting him of two felonies and two other misdemeanors. His bail was raised to fifty thousand dollars and he now faced a certain prison sentence (Melnick, 2010).

Following his conviction, Morrison filed an appeal and he and the band would spend the uncertain winter of ’70-’71 recording their sixth and final album together, L.A. Woman.

Just prior to the full commencement of the L.A. Woman sessions, On Tuesday December 8th, Jim Morrison would spend his 27th (and final) birthday at another recording session held exclusively for his poetry. Although the majority of these recording remains unreleased, on this day he would recite a devotional poem titled, Science Of Night.

December 8, 1970.

————————————————(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Four days later at “The Warehouse” in New Orleans, The Doors would play their final live concert together. Halfway through this show Morrison seemed at first distracted and then just completely spent. After slumping down on to the floor, Morrison grabs the mic stand and continually slams it into the stage eventually splintering the wood. Then throwing the stand aside he leaves the stage. Ray Manzarek later states that he witnessed at this show all of Morrison’s “psychic energy” abandon his body.

Jim Morrison at The Doors last performance, December 12, 1970 at The Warehouse in New Orleans, LA.

L.A. Woman sessions (photo by Frank Lisciandro)

In preparation for a new album, over the next few weeks that followed their final performance The Doors would convert their office and rehearsal space—The Workshop, located at 8512 Santa Monica Boulevard in Los Angeles—into a recording studio. Despite numerous detriments at the time, L.A. Woman would be an artistic triumph. Recorded and mixed in only two weeks, and although these sessions were for the most-part a relaxed affair, it would feature some sublime and manic moments as on the title track, as well as marvelously rough recorded booze-soaked blues as on “Cars Hiss by My Window.”

——————————————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Like it? Buy it?

This album would also feature some of Morrison’s most direct and plaintive lyrics:

I need a brand new friend who doesn’t bother me.

I need a brand new friend who doesn’t trouble me.

I need someone who doesn’t need me.

(“Hyacinth House”).

Here is that song recorded as a demo at guitarist Robby Krieger’s home studio:

—————-(CLICK TO LISTEN)

Like it? Buy it.

Jim Morrison would be dead within six months of these recordings.

L.A. Woman sessions (photo by Edmund Teske).

In the hopes of some respite from the threat of imprisonment, as well as a desire to escape his rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle for some time and concentrate on his writing once more, Jim Morrison and Pamela Courson relocated to Paris on March 11th 1971. At the time, he told The Doors’ manager Bill Siddons, “I don’t know who I am, and I don’t know what I’m doing at the moment. I even don’t know what I really want, I just wanna go away” (Moddemann, 1999).

Wandering Paris

Moving to No. 17 Rue Beautreillis, Morrison placed a desk near the window in order to write at. Spending the majority of his time wandering the streets, Morrison carried his notebooks in a bag at his side at all times.

So much forgotten already

So much forgotten

So much to forget

Once the idea of purity

born, all was lost

irrevocably

[…]

And I remember

Stars in the shotgun

night

eating pussy

til the mind runs

clean

[…]

A monster arrived

in the mirror

To mock the room

& its fool

alone

Give me songs

to sing

& emerald dreams

to dream

& I’ll give you love

unfolding

[…]

Naked we come

& bruised we go

nude pastry

for the slow soft worms

below

This is my poem

for you

Great flowing funky flower’d beast

Great perfumed wreck of hell

Great good disease

& summer plague

Great god-damned shit-ass

Mother-fucking freak

You lie, you cheat,

you steal, you kill

you drink the Southern

Madness swill

of greed

you die utterly & alone

Mud up to your braces

Someone new in your

knickers

& who would that be?

You know

You know more

than you let on

Much more than you betray

Great slimy angel-whore

you’ve been good to me

You really have

been swell to me

Tell them you came & saw

& look’d into my eyes

& saw the shadow

of the guard receding

Thoughts in time

& out of season

The Hitchhiker stood

by the side of the road

& leveled his thumb

in the calm calculus

of reason.

(excerpts from Paris Journal by Jim Morrison)

Wandering Paris on June 17th, 1971, Morrison came across two young American street musicians who were playing guitar in front of the Café de Flore. The three, getting drunk throughout the day, would rent an hour from a little local recording studio and attempt to “jam.” Morrison would tell the engineer it was his own band called Jomo And The Smoothies. “I get twenty-five percent of everything that happens, right?” he asked the other two musicians (Moddemann, 1999). However, these two new acquaintances failed to take any of it remotely seriously, despite Morrison’s repeated attempts to get them to settle down into any song. Eventually he would suggest one of his own more recent compositions and would begin to drunkenly, yet passionately bellow and croon his way through his ode to Pamela, “Orange County Suite”:

June, 1971 photo by Alain Ronay

——————————————————————(CLICK TO LISTEN)

[Note: this track has been edited by me to remove much of the incessant and amateurish noodling of the other two musicians and focus upon what would be Jim Morrison’s final recorded performance]

For those who have been wondering why a discussion of Brian Jones has somehow transformed into a lengthy discussion of Jim Morrison and his work: two weeks after the above recording was made, and exactly two years later to the day of Brian Jones’ death, On July 3rd 1971 Jim Morrison was found dead in the bathtub of his Parisian apartment by his girlfriend Pamela. He was also only twenty-seven years old. They had spent the evening of the 2nd at the cinema watching a western starring Robert Mitchum, titled Pursued. Returning to their apartment at about 1.00 a.m. on July 3rd, Morrison sat down at his desk and attempted to write but could not concentrate. Instead they watched some Super 8 films of a recent Moroccan vacation and listened to old Doors albums. Afterwards the couple went to bed.

Plagued by coughing fits for weeks now, Morrison woke up and vomited. There were traces of blood within it. Not wanting to call a doctor, Morrison sent Pamela back to bed, and filled up the tub for a hot bath. The last thing she remembered hearing him say was, “Are you there, Pam? Pam, are you there?” Later that morning she found him submerged in the water with a smile on his face. At first she thought he was playing a joke. No autopsy was performed and the official cause of death was listed as “heart failure.”

Epilogue:

Exactly forty-two years after Brian Jones’ death, and exactly forty years after Jim Morrison’s death—on a rainy afternoon in the town of Big Indian, located in upstate New York, My wife and I were married. Everyone made it through to the other side of that wet day just fine.

———————-Bobby Calero——————————–

Epstein, D. M. (2011). The Ballad of Bob Dylan. New York: Harper Collins.

Greenfield, R. (2006). Exile On Main St.: A Season In Hell With The Rolling Stones. Philadelphia: Da Capo

Hill, C. (2011). The Lost Boy. The Bluegrass Special. Retrieved from http://www.thebluegrassspecial.com/archive/2011/july2011/brian-jones-rolling-stones.html

Jones, S. (2008, Nov. 29). Has the riddle of Rolling Stone Brian Jones’s death been solved at last? The Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-1090439/Has-riddle-Rolling-Stone-Brian-Joness-death-solved-last.html#ixzz1z12zlGI5

Marcus, G. (2011). The Doors: A Lifetime of Listening To Five Mean Years. New York: Public Affairs.

Melnick, J. (2010, Sept. 20). Back in the Day: Jim Morrison Convicted of Indecent Exposure. Beached Miami. Retrieved from http://www.beachedmiami.com/2010/09/20/day-jim-morrison-convicted-indecent-exposure-sept-20-1970/

Moddemann, R. (1999). Jim Morrison’s Quiet Days In Paris. The Doors Quarterly Online. Retrieved from http://home.arcor.de/doorsquarterlyonline/quietday.htm

Morrison, J. (1969). The Lords and The New Creatures. New York: Touchstone.

Morrison, J. (1990). The American Night. New York: Vintage Books.

Morrison, J. (1988). Wilderness. New York: Vintage Books.

Wenner, J. (1995). Jagger Remembers. Rolling Stone.

Wyman, B. (2002). Rolling With the Stones. England: Dorling Kindersley.